Response to Mike Gantt Review

Mike Gantt has written what he seems to think is a scathing review of my book. (It is a review in twelve parts, and begins here.) He has stated on numerous occasions that I won’t be “very pleased” with what he has to say. In response, I’ll start by stating up front that it’s not that I’m not pleased with the criticisms he makes of my book because they’re good criticisms. I’m not pleased with them because they were a complete waste of my time, many of them bordering on unintelligible. His review is long; I’ll give him that. But part of that is due to the repetition of assertions that appeal only to people who already share his views, and that will otherwise persuade no one else. In reality, many of Gantt’s criticisms don’t even apply to my book. He has beaten a number of straw men; he has concocted claims I am supposed to have made; he has displayed a predilection for guessing at my unspoken motives, and in every case, he has misdiagnosed me. It’s really a sad review. So why am I responding? Honestly, because I’m bored, and because I’m procrastinating on projects I ought rather to be doing. With that said, I’ll get to the blah blah blah, whatever.

[DISCLAIMER: My response to Gantt’s review is full of sarcasm. If you’re offended by sarcasm, don’t read the response. It’s as simple as that. In all honesty, it was the only way I could get through this. Call it a character defect if you will. I call it therapeutic. If Gantt had been a little less confident in his armchair diagnoses of my motives, and a little less prone to flagrant caricature of my views, I’d have written a really nice response with all the cordiality appropriate to a constructive dialogue. But since Gantt’s review was more deceptive than constructive, I gave him the responses his criticisms deserved, in my opinion. If you have a different opinion, you’re welcome to it. I’m not really looking for a discussion about it though. I’ve already wasted enough time as it is. So you’ve been warned. By continuing to read, you agree (a) not to be offended by my sarcasm, or (b) that you won’t complain to me about it if you are. If you complain, you’re in violation of the agreement requisite for the reading of this blog post. ]

RESPONSE TO GANTT’S INTRODUCTION

I am concerned that Thom’s book is obscuring more truth than it is presenting.

That’s a valid concern. Let’s see if it’s my book or Gantt’s review of it that’s doing the obscuring.

As you can tell from the title, the endorsements, the foreword, and the preface, this book presents a liberal Christian view and is an argument against conservative Christianity.

So says Gantt, repeatedly. I’m a “liberal” and the objects of my criticism are “conservatives.” Gantt seems to find these labels useful, even revelatory, throughout his review. But we’ll see as we progress why Gantt’s use of them only serve to obscure the reality of the situation.

My purpose in this review therefore is to stand up for Jesus Christ and for the Scriptures. I believe Thom’s book is destructive of faith in both, even though he may not intend it to be so.

There you have it. At least he’s honest. Gantt’s objective is not to provide an objective analysis of my book, but to “stand up for Jesus Christ and the Scriptures,” because he thinks my book is “destructive of faith in both.” No further comment.

Starting with the subtitle, I do not believe that Scripture “gets God wrong.” Rather, I think we sometimes get Scripture wrong. There’s a world of difference.

I’m glad to know where Gantt stands.

Thom’s great foil in the book is the Chicago Statement of Inerrancy. As I said, I don’t want to intervene in his argument with fundamentalism. Therefore, I’m not interested in defending the Chicago statement (or condemning it either, for that matter). However, I am intensely interested in defending the point of view that Jesus put forth about the Scriptures.

Among other things, Jesus said,

“Scripture cannot be broken.” – John 10:35He also said something like “even the dots of the i’s and the crossings of the t’s are important” in Matthew 5:17-19. And in Luke 24: 25 “O foolish men and slow of heart to believe in all that the prophets have spoken!” (italics mine). And there are more references to which we could turn, but I’ll stick with the short and sweet “Scripture cannot be broken” as representative of Jesus’ view.

Think of it this way: Jesus believed that the Scriptures are the word of God. God cannot lie. Therefore, God cannot contradict Himself. Therefore, the Scriptures cannot contradict themselves.

Thus, the view of Thom’s book is at odds with the view of Jesus. I have to choose the view of Jesus as more reliable.

Well, there you have it. Jesus and Thom have different views of Scripture, and so it’s for Gantt a choice between who is more trustworthy—Jesus or Thom. For Gantt it’s a no-brainer. Apt.

Never mind that I discuss at some length Jesus’ view of and usage of scripture. Never mind that I directly confront the issue of whether Jesus’ view of scripture is something we must adopt just because it belonged to Jesus. Let’s ignore all that and appeal to his readers’ loyalty to Jesus.

I have no problem acknowledging the diversity of the Bible’s writings and its authors. But that’s what makes its unity all the more striking. Thom’s book will say that the Bible has many voices. I agree, but where he hears cacophony I hear harmony. And when the subject is Jesus Christ those voices come together in unison: He is the promised Messiah, the Son of God!

If you’re going to follow along to the end, you’d better get used to bald assertions like these from Gantt, and to my non-responses to them.

RESPONSE TO GANTT’S REVIEW OF CHAPTER ONE

The title of Thom’s first chapter is The Argument: In the Beginning Was the Words. The point Thom tries to make with this chapter is not just that the Bible contains contradictions, but that it is characterized by them. Wow. I’ve heard people say that the Bible is filled with contradictions (I used to say that myself – before I started reading it), but Thom gets really bold and says it’s so full of competing views that it should be called “the Argument” or “the Words” instead of the “Word.”

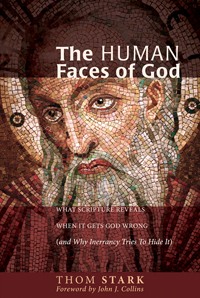

What this displays is that Gantt has little to no familiarity with mainstream biblical scholarship. He writes as if this idea were original to me. I’m “really bold” for saying it. Gantt has heard lesser claims, but not the one I make! In other words, Gantt isn’t writing from an informed position. Hell, I quote (believing scholar) John J. Collins to the same effect on the very first page of chapter one. That the Bible is comprised of books arguing with themselves is just taken for granted among biblical scholars. But it’s news to Gantt’s ears, and radical news at that. How about that!

To say that the chapter fails to make its point is to give it too much credit. It is spectacularly unconvincing. It’s clear that Jesus and His apostles did not view the Bible the same way that Thom does.

There you go. Case closed, folks.

It is Thom who contradicts the Bible, not the Bible which contradicts itself. How does Thom contradict it? How about starting with the first sentence of this chapter. In it he alludes to John 1:1, and changes “Word” to “Argument.” In other words, where the apostle John wrote “Word” Thom says “Words.” So, in trying to demonstrate that the Bible contradicts itself, Thom begins by misquoting it.

I’m doing my best to refrain from using certain descriptive nouns here. The nicest way I can think to put it is that I think something important might have eluded Gantt here. Well, a couple of things. “Argument,” first of all, is a perfectly legitimate translation of the Greek word logos. But that’s not my point. That’s just my Greek pun. My point is that before the Scriptures came to be seen as a singular Word, they were really an argument with themselves. That’s a point I make very explicitly. I never would have imagined that anybody would have read my opening sentence and thought that I was trying to fool people into thinking that John meant, “In the beginning was the argument.” But I hadn’t been introduced to Mike Gantt when I wrote that sentence. Had I had Gantt in mind when I wrote the sentence, perhaps I would have included an explanatory footnote, stating: “And here I’m not quoting John, but playfully alluding to him.” I apologize for not realizing the playfulness of my allusion wouldn’t be obvious to everyone. Well, no I don’t. My apology is just as playful.

Thus the contradiction lies between Thom and the Bible, not between the Bible and itself.

A stunning demonstration of the fundamental flaw underwriting my book. Well done, Mike.

In golf, they say you should play the ball as it lies. Thom, however, prefers to pick the ball up and place it on some tuft of grass that gives him a chance to really whack it. That is, he just changes the words of the text to suit the point he wants to make. Not only that, he changes the words so that they will mean the exact opposite of what they meant as written. Thom wants to say that “the Bible is an argument with itself” so he takes a passage that says that the Bible has a clear and focused message about Jesus Christ and changes it to say that it is an argument with itself.

Another awe-inspiring and incisive criticism of my modus operandi.

Let us, however, give Thom the benefit of the doubt and assume that he’s not trying to mislead, nor even trying make his point, with these initial words. Let’s assume he’s just introducing the subject in a novel way.

Oh wait. After accusing me of “changing the words of the text to suit the point I want to make,” Mike offers . . . a retraction? A what? I’m not sure. I’m confused. Should I be mad at myself for playing fast and loose with the text, or amused with myself for a good pun? I’m in the dark here. Help!

Thom sets up a hypothetical conflict between Ezra and Amos because he reads ethnocentric strains in one and universal strains in the other. But it’s just that – a hypothetical argument, existing only in Thom’s mind – not in the pages of Scripture.

Gantt seems to think I imagine Ezra and Amos duking it out in a bar. That sure would be something! But no, the argument exists not between the historical persons of Ezra and Amos, but between different schools of thought, schools of thought which Gantt goes on to attempt to reconcile:

How can ethnocentrism be reconciled with universalism? Easily. God chose Abraham that all the nations might be blessed through him. The focus on Abraham is ethnocentric and the focus on the nations is universal. Thus the ethnocentrism is for the sake of promoting universalism. The former is pursued in service of the latter. The Messiah had to be from the line of David precisely so that all folks – whether of the line of David or not, could be saved. Ethnocentrism and universalism are not at odds with each other in the mind of God. They complement one another by virtue of the fact that the former is the means and the latter is the end.

Perfect! Well done, Gantt. Now, let’s just see you reconcile Ezra’s actual view of non-Israelites, not the view you’ve pulled from other sources.

Next, Thom attempts to offer another “contradiction,” this time bringing in the book of Jonah as representative of the universal focus of God, and suggesting that Ezra and his colleagues – by contrast – wanted to “hide [Israel’s] light under a bushel.” Nothing in the book of Jonah challenges the book of Ezra, nor does Ezra challenge Jonah. Thom just reads this “argument” into the text. The only readers persuaded by this sort of thing are those who are looking for confirmation of their belief that the Bible contains contradictions.

More assertion without argumentation, more ignoring of the substantive textual issues in my own argument. As for the last claim above, in fact, I was a reader expecting to find unity when in fact I found contradiction. And all of my efforts to reconcile the apparent contradictions did not hold up. But whatever. It’s easier for Gantt to believe that those who disagree with him just believe what they do because they have a confirmation bias than for Gantt to admit to his own. (I’ll refer him to his own words about what’s motivating his review in the introduction.)

Like any good parent, God fashions His counsel around the circumstances and needs of His children. If you have child who has a messy room, you talk about the value of an ordered room. On the other hand, if the child spends too much time in the room, you encourage him to get out and play with the other children. There were times in Israel’s history when they were too myopic and thus forgot their role as a light to the nations. In those times, God nudged them to look outward to the Gentiles. At other times, Israel lost sight of the need for its own purity – for how could they be a light to the Gentiles if they themselves were abiding in darkness? It’s as if Thom has never read Ecclesiastes 3 (“there is a time for [this}, and a time for [that]). It’s like Thom is insisting that there is a contradiction between summer and winter or that there is a contradiction between day and night. These are not contradictions; they are different states of being. God speaks to us according to the need of the moment (Ephesians 4:29). As the needs change, His emphasis to us changes.

Well done again, except for the details of the actual texts in question (all of which you fail to mention). If you the reader want to know the details, see my book (and not Gantt’s review, where they don’t make an appearance).

Next, Thom tries to suggest that Job and Ecclesiastes are “subversive” to the rest of the Bible. Huh? Let’s take them one at a time. If you are looking for an argument in the Bible, we certainly have one in the book of Job. But it’s not God giving conflicting ideas about Himself, it’s human beings arguing about God’s ways. The fundamental point of the book of Job is that while it’s true that God rewards the righteous and punishes the wicked, there is such a thing as undeserved, or at least unexplained, suffering (which foreshadows what will happen to Messiah), and, in any case, we can’t always understand the workings and justice of God in this life because of our limited human perspective.

This would be great if it were actually what Job is saying. But in fact, it’s not. Job says that God was the author of Job’s undeserved misfortunes. Moreover, this would be all great except that it misunderstands the Deuteronomistic perspective against which Job is arguing, namely that all misfortune is a punishment for sin. Hence the concoction of some minor sin on Josiah’s part to explain his very unexpected and anticlimactic death in battle in the Deuteronomistic History. Again, Gantt just isn’t read up on the scholarly literature.

This is why Ecclesiastes says, “Although a sinner does evil a hundred times and may lengthen his life, still I know that it will be well for those who fear God, who fear Him openly” (8:12). And for all the Teacher’s supposed despair in Ecclesiastes, he ends with “The conclusion, when all has been heard, is: fear God and keep His commandments…because God will bring every act to judgment…” (12:13-14). Those are not the words of a hopeless man. Moreover, why would he say such a thing if, as Thom suggests, resurrection was off the table?

I’m starting to wonder if Gantt even read my book. Did he? If he did, he’d realize that 12:13-14 weren’t written by Qohelet, but by the editor. Hell, if he even read Ecclesiastes itself he’d realize that. Because just four verses earlier (12:9), the author clearly shifts from Qohelet to the editor. Qohelet’s own conclusion, Mr. Gantt, is that everybody dies, and that, “vanity of vanities, all is vanity” (Eccl 12:8). The editor, who wrote later and added vv 9-14, clearly had a different perspective to push.

As for 8:12, Gantt seems to think this speaks to an afterlife or something. Sorry. It doesn’t. All it says is that God will look after those who fear him. But, unlike Proverbs (which it is countering), it acknowledges that sinners often prosper more than the righteous, which isn’t fair. That’s Qohelet’s whole point throughout. Perhaps Gantt missed it.

I could go on, but Thom simply invents “contradictions” and “arguments.” He fails to see the rich tapestry that is the Bible, instead seeing various strands of color that seem to him as clashing.

I could go on, but Gantt simply ignores my actual arguments, so why bother? Oh right. Because I’m bored and procrastinating.

He seems to want the Bible to read like a grade-school catechism or an FAQ page. And if it doesn’t, then it must be contradictory.

Right! That’s it, Gantt. You’ve nailed it.

In the closing section of this chapter, Thom narrates his view of how the Hebrew Bible came together. He assumes Wellhausen’s Documentary Hypothesis (or some variation thereof) which insists that Moses couldn’t possibly have written the five books attributed to Him. Yet Thom just assumes this without offering proof for it. And against it we have the view of Jesus who said, “If you believed Moses, you would believe Me, for He wrote of Me” (John 5:46).

There we go. Now it’s Jesus versus Wellhausen! Who are you going to trust, Christians?! Where do your true loyalties lie? Of course, the DH doesn’t “insist” that “Moses couldn’t possibly have written the books attributed to Him” (why are we capitalizing the Mosaic personal pronoun?). It demonstrates on hundreds of levels that he didn’t. And these findings are backed up by philology to boot. Gantt is going to make frequent reference to my “assumption” of the DH. I’m curious to know which proponents of the Documentary Hypothesis Gantt has read, and where his exhaustive, consensus-overturning criticisms of JEDP are to be found in publication. Certainly his contributions will be of much benefit to the scholarly community.

Do you notice when you read the gospels that Jesus just doesn’t seem torn and troubled about “contradictions” in the Law and the Prophets? On the contrary, He seems to think they are the word of God and is constantly saying that “such and such must happen in order that the Scriptures be fulfilled.” If it’s just a bunch of arguments, how could it ever be fulfilled? Was the Messiah to be a schizophrenic?

This is one of the unintelligible criticisms I referred to above.

Thom’s view of the Scriptures and Jesus’ are diametrically opposed. Thom wants to make a case that we should accept his view, but he only offers a few contrived and artificial “contradictions.” Thus, as I said at the outset of this post, Thom fails spectacularly to make the point he sets out to make in this chapter. Had he tried merely to say that there are parts of the Bible hard to understand, that some parts are more easily reconciled than others, or that diversity of writings and writers sometimes staggers the comprehension – any of these conclusions, I could have supported. But Thom chose to go much farther than that. He chose to mis-characterize the Bible and thus discourage faith that it has a unifying voice in the Holy Spirit. This is not right. I must speak against it.

Speak, brother! Speak!

I have written bluntly. I respect Thom as a fellow human being, but this first chapter portrays the Bible falsely and it does not seem appropriate to mince words in saying so. Thom is bringing his assumptions and reading them into the text. He is accurately reporting on what he sees when he reads, but he’s seeing through unclear lens of his own choosing. Set them aside and let God speak for Himself to you through the Holy Scripture.

Preach it!

Prophets wrote and spoke the words of Scripture at risk of their own lives. They have borne witness with their blood.

As did most of the false prophets too.

What the Holy Spirit whispered in their souls, they have spoken boldly to the world. Let us not dishonor their sacrifice. Nor let us dishonor the One of whom they spoke so highly…and so consistently: the Holy One of Israel.

And while we’re at it, let’s give three cheers for the troops out there putting their lives on the line to protect our freedoms. A moment of silence if you will.

RESPONSE TO GANTT’S REVIEW OF CHAPTER TWO

In this chapter, Thom, a liberal Christian, takes to task his conservative Christian brethren.

Let it be known to all that Thom is a liberal Christian.

As I said in the introductory installment of this book review, I have no interest in their intermural arguments. There are liberal Christian seminaries and conservative Christian seminaries, and within some seminaries you’ll find a contingent of each category. The main point of dispute Thom chooses, as we’ve seen, is the “Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy.” While I don’t want to dwell on this internecine warfare between the left and right wings of Christianity, I should give a warning to you about Thom’s writing.

You have to read Thom carefully to avoid being misled. For example, in his excursus on Daniel he begins by saying “Although the book of Daniel is set in the sixth century BCE, critical scholars are virtually unanimous that it was not completed in its final form until the mid-second century BCE.” You might get the idea from this there are hardly any scholars who accept Daniel at face value. However, that word “critical” in his sentence might not have caught your eye. It should have, because “critical” in this case is a synonym for “liberal.” This is a point which Thom inadvertently confirms himself when, near the end of the excursus, he writes, “Inerrantists frequently make the claim that ‘liberal’ scholars argue for a ‘late date’ for Daniel…” – that late date being the one he specified: mid-second century BCE. For some reason Thom doesn’t seem to like the label “liberal.” But note that he’s describing a conflict of views between liberal and conservative scholars. Only the way he presents it, especially if you’re not reading with the greatest of care, it comes across like virtually all reputable scholars are unanimous about something that only some knuckle-dragging, Neanderthal “inerrantists” dispute.

This is where Gantt thinks using these labels is revelatory. Of course, he hasn’t a clue what he’s talking about. “Critical” scholar and “liberal” scholar are far from synonymous. There are a host of conservative scholars who are appropriately identified as critical scholars. Let’s take N.T. Wright for instance. He’s a conservative scholar who is for the most part a critical scholar. N.T. Wright accept the consensus on the dating of Daniel, and even uses that consensus position to mount arguments in his own book (especially his book on the Resurrection). So, let’s not be deceived by Gantt’s claim that I’m trying to deceive you. When I said, “critical scholars,” I didn’t mean, “liberal scholars.” I meant just what I said: “critical scholars,” among whom some are more “liberal” and others are more “conservative.”

By the way, I am using the terms “liberal” and “conservative” Christian [in] a descriptive, not a pejorative, way. While Thom sees those Christians to his right in a negative way, I see both liberal and conservative Christians believing what they think is right. I can learn from both of groups, even though I do not consider myself a member of either.

I don’t know which “Thom” Gantt is referring to here, but it isn’t me. Rather, I see everybody in a negative way. I think it’s genetic.

Another warning I’ll give you is that Thom says one thing but then does another. For example, he begins this chapter with “It is not my intention to demonize inerrantists.” If that’s his intention then I’d say he can demonize better unintentionally than most people can intentionally.

Another bit of sarcasm lost on Gantt. Woe is me. Perhaps I’m just a very poor writer? No, that can’t be right, because Gantt says, “The Human Faces of God is well-researched and well-written. Thom Stark is intelligent, educated, and articulate.” Once again, I’m left confused about what to think of me.

Thom defines an inerrantist as “someone who believes that everything the Bible affirms is true, and good, and that it comes from the mind of a kind, loving, merciful, and just God.” He goes on to say such a person does not exist. I have a candidate: Jesus Christ. Does Thom – does anyone – think that Jesus did not regard the Bible as true, and good, and as coming from kind, loving, merciful, and just God?

Uh, no you don’t. Let’s try quoting me in context. What I demonstrate is that nobody who claims to believe that about the Bible is able to affirm it in the details, and as I showed, Jesus himself disagreed with numerous biblical authors, not least Qohelet’s view of life after death.

If Jesus believed what Thom believed about the Bible, Jesus would have taught about it what Thom teaches. Instead, He prayed to God saying, “Thy word is truth” (John 17:17). Jesus believed that the Scriptures spoke what was “true, and good, and that it all came from the mind of a kind, loving, merciful, and just God.” That’s good enough for me.

Terrific! I’m glad Gantt has this settled in his mind. Now, with Gantt’s permission, the rest of us are going to continue the conversation.

By the way, Thom spends much time in this gospel comparing and contrasting various methods of interpretation. In doing so, he displays his scholarship. He is not only a good writer, he is well-educated. He handles history, linguistics, and other disciplines with ease. His prose is so fluid that the various disciplines coalesce into a narrative that is easy for the less-educated to follow. In fact, he reminds me of Bart Ehrman – another, albeit older, scholar who is able to translate academic knowledge for mass consumption. Thom and Bart are taking what has long been known in the academic world and presenting it in popularly written terms for lay people. Unfortunately, both have the same effect on their readers: to encourage the unbelievers and discourage the believers.

Um, shall I provide documentary evidence to the contrary? OK. I will:

(4) Michael J. Izbicki, Review of “The Human Faces of God” in Anglican Theological Review 93/2 (Spring 2011): 362-63.

And so on…

This is because both are simply repackaging the long-held liberal view of Scripture which is, generally speaking, less committed to the idea that the Bible is the word of God than the conservative view.

Oh, are we still claiming that my book has only had a negative effect on the faith of Christians?

Therefore, we have Jesus meeting Thom’s definition of an inerrantist. This leaves Jesus in stark contrast (no pun intended) to Thom, the errantist.

By Gantt’s definition, Jesus was an inerrantist. My point (which remains correct) is that Jesus would not have been a consistent inerrantist.

Thom doesn’t call himself, or those others who think like him, an errantist, but given that Thom’s book is a polemic against inerrantists there could be no more appropriate label.

OK. Call me an errantist. Just don’t call me late for happy hour.

Even though Jesus meets Thom’s definition of an inerrantist,

Nope. He meets Mike’s definition, not mine. But whatever…

the term doesn’t really speak adequately to the issue. That is, someone who believes that the Bible is “true, good, and comes from the mind of a kind, loving, merciful, and just God” is saying much more than simply “I don’t think the Bible has errors.” Such a person goes to the Bible expecting to find the voice of God through a variety of human voices. A person like Thom, on the other hand, expects to hear arguments and contradictions about God, with any voice of God therefore much harder to find.

Now I do. Yes. When I found the contradictions in the text, no. I did not expect to find them. So there goes that whole, well, whatever that is.

Practically speaking, all agnostics and atheists are errantists. That is, they don’t believe the Bible is wholly true as Jesus did. As we have seen, liberal Christians, like Thom, are also errantists but do believe in some parts of the Bible – though they vary on how much and which parts. The odd thing to me is that Thom seems to feel much more comfortable with other errantists – regardless of their stripe – than he does his own self-confessed fellow Christians. Likewise, atheists and agnostics have professed affinity for Thom’s book (notably John Loftus and Ed Babinski, both self-professed former Christians). Thus I am puzzled that while Thom professes an allegiance to the cause of Christ, he writes a book that is extolled by those who are against Christ.

Oh, I see the confusion. Gantt assumes an allegiance to the cause of Christ commits one to an allegiance to the integrity of the Bible. I don’t hold that assumption. See, my allegiance is to truth, first and foremost. And my allegiance to the cause of Christ (namely, to bring good news to the poor, to proclaim release to the captives, recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free) is derived from my allegiance to the truth. I have allegiance to the cause of Christ because Christ’s cause is true, not because it’s Christ’s. I imagine Gantt finding that statement revelatory, but for him it should just be a tautology, if he thinks for a moment, and therefore nothing very revelatory at all. Anyway, I’m happy if anybody finds my book useful for dispelling falsehoods. I don’t care if they’re atheist, agnostic, Christian, Muslim, Jewish, or drug dealers. Of course, how they use my book is up to them, and I don’t bear responsibility for its abuse. But if an atheist wants to point out to a fundamentalist Christian that they live in a house of cards, and my book is useful for that purpose, great! Let the truth be known. Each person is responsible for what they do with the truth when they find it. Needless to say, at any rate, I don’t find these guilt by association insinuations very interesting.

Presumably, Thom believes that Christians can be either inerrantists or errantists, and further that being an errantist Christian is the better way to be. I might disagree with Thom on this point, but it would not be an unreasonable one for him to make. However, that Christ meets his definition of an inerrantist introduces a dilemma for his claim.

Not really, and if Gantt had read my book closely he’d see why the claim he’s repeatedly making doesn’t hold water. The least he could do, of course, would be to engage my discussion in which I directly engage this question. But no. For whatever reason, Gantt isn’t interested in an actual engagement with my actual positions. He prefers caricature, which is a fine art form. I have nothing negative to say against that if that’s his aesthetic preference; it’s just not very useful in a book review format. But again, I make no judgments.

If you love Christ, then you proclaim with Paul “Whether in pretense or in truth, that Christ is proclaimed, in this I will rejoice.” Or, if you will, “Whether in errancy or inerrancy, Christ is proclaimed, in this I will rejoice.” Thom, however, seems more intent on proclaiming errancy than in proclaiming Christ. And that’s troubling.

Yeah, or, Thom believes that inerrancy is a roadblock to proclaiming Christ truthfully. Either one. I’ll defer to Gantt’s judgment. I know what I mean less and less the more I read Gantt’s review.

RESPONSE TO GANTT’S REVIEW OF CHAPTER THREE

In the previous installment, I employed the term errantist to describe Thom’s point of view in contradistinction to the inerrantists against whom he argues throughout the book. For clarity, I’ll continue to utilize this in order to make clearer Thom’s intent.

Oh wait. Now Gantt is claiming that the label “errantist” makes “clearer Thom’s intent.” No, not really. “Realist” would be a better label to that end.

I also pointed out that Jesus Christ meets the definition Thom laid down for an inerrantist: “someone who believes that everything the Bible affirms is true, and good, and that it comes from the mind of a kind, loving, merciful, and just God.”

Yes, he pointed this out mistakenly, because he misconstrued the broader context in which that definition appeared.

I am solely interested in defending Jesus the inerrantist, as well as the Bible itself, from Thom’s attacks. (Make no mistake, Thom’s book is an attack on the credibility of Jesus and the Bible.)

Not really. In point of fact, it’s an attack on an approach to Jesus and the Bible which is a disservice to both Jesus and the Bible. Anyone (other than the Gantts of the world) who reads my book will realize that my goal is to offer a better way to read the Bible, a way that respects and reveres it more robustly than does the doctrine of inerrancy, which really offers only a pseudo-respect, an all-or-nothing conditional reverence which is more fitting of adolescents than mature adults.

The first argument Thom makes in this chapter is that the Bible is not a self-aware or sentient being. Jesus didn’t teach that it was, nor does anyone else I know, so Thom is arguing with a straw man of his own making.

#facepalm.jpg

I love it. A strawman about a strawman. In reality, the point I made is that “the Bible” doesn’t speak about “itself,” but rather that certain authors speak about certain other texts.

Though Thom doesn’t admit it, the canon of the Hebrew Bible was never an issue in the New Testament. Everyone – whether for Jesus or against Him – referred to “the Scriptures” or “the Law and the Prophets” without arousing the sorts of arguments Thom thinks are so relevant.

The reason I don’t admit it is because it isn’t true. There were a number of books whose canonicity was debated or rejected by Jews during and even after the time of Jesus.

People knew what the Scriptures were. That canon of books has not changed in 2,000 years. There are some branches of Christianity (notably Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox) which add some books to the core Old Testament canon, but there is no dispute about what books constitute the core canon.

Gantt should inform the Sadducees and the Council of Jamnia about this!

Thus Jesus was presented a Bible, and its contents were settled enough that He never felt the need to address the subject.

Probably why I didn’t feel the need to address the subject either. Which leads me to some confusion about why Gantt is addressing the subject that I didn’t address. Oh right. He’s addressing it because I am deceptive by not admitting that Jesus had a fairly fixed set of scriptures.

We don’t have to either.

Wait. Never mind. He’s not addressing it.

Next, Thom argues that just because the Bible is inspired by God does not mean it is without error. All I can say to that is if God is inspiring error then there’s no hope for any of us. How can you rely on what He says if He’s prone to error?

All I can say is, it would be nice if Gantt were to engage the actual arguments I make in support of the claim he quotes, you know, at least so as to give his readers some perspective on what I actually mean by what I say.

Thom goes on to argue that just because the Bible is authoritative does not mean it is error free. That is a distinction without a difference. For the Bible to be authoritative as the word of God, it must be presumed to be without error insofar as God spoke what we’re reading.

If you say so, Gantt. I guess everything I said about the question is irrelevant, since everything I said makes no appearance in your “critique.”

To say that we’re reading the word of God but He might be wrong about some of the things He says, sort of undermines the authority, eh?

I suppose you’re right, Gantt. Where should I send my retraction?

Now, we have to quickly acknowledge that we are reading texts in languages other than the ones they were originally written in, that we’re thousands of years removed from the people who wrote them, and that we’re reading copies of what they wrote. So, could there be errors on the page in front of us even though they weren’t there when the prophet wrote them? Yes. And you could add to that the errors in our minds that cause us to misunderstand what we do read. However, what makes us continue to read is the belief that beneath all the intermediate steps, there are words that God wanted us to hear. And, more practically, though we may misunderstand a sentence here or a section there, we will be able to find themes in what is written that will come through clearly, especially when repeated by various writers in various ways. ”Out of the mouths of two or three witnesses, let every fact be established.”

With that last quote Gantt must be exampling what it looks like to misunderstand a text’s meaning, you know, for clarity.

The accounts of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John are not identical. If they were, you could throw away three of them. As it is, they complement each other. They each see Christ from a different perspective. All are inspired by God, but limited by human perception. I have four children. If you were to ask each of them to write a short narrative of my life as they have known it, you could get four similar, yet somewhat differing, accounts. And that’s just what we get in the four gospels. Their diversity does not mean there are errors; rather, the diversity gives us a fuller picture.

Correct. Their diversity does not mean there are errors. Rather, their errors mean there are errors. This is an important distinction and I’m glad Gantt took the time to make it.

I suppose someone could nitpick the biographies by my four children and find seeming points of discrepancy. But that’s all they’d be – seeming points of discrepancy, not actual ones.

Because Gantt’s children are inerrant?

Thom’s style is to pick every seeming point of discrepancy and make as much out of it as possible.

I must have a really awkward style.

Instead, our intent ought to be to find Jesus – to take every piece of data we find in order to receive the mosaic picture the Bible has given us of Him. And as we look to the gospels to do this, so also we should look to the rest of the New Testament, for it, too, is about Him. And do not forget that we should do exactly the same with the Old Testament, for though it was initially written to guide the nation of ancient Israel, its ultimate purpose was to reveal Christ to the world (John 5:39).

This is the word of the Lord. ______ __ __ ___.

“A Legal Controversy” – Thom tackles Matthew 5:17-18, which is a difficult passage for errantists.

For errantists or inerrantists?

His first tack is to sow doubt that Jesus ever said it (A most convenient debating tactic, and one that is easy for an errantist to employ).

Well, I offer a reason for the doubt, but in point of fact my view is that Matthew’s version of the logion is probably original to Jesus, and that Luke changed it for his own purposes. I just don’t say that in the book because which version was original to Jesus is irrelevant to the point I was making.

Then he tries to show that inerrantists aren’t consistent in their interpretation of it (So what? That has nothing to do with Jesus’ faith in the Bible). Lastly, he tries to suggest that Jesus was intentionally leaving out reference to “the Writings” (Puhleeze!) Thom’s goal in each case is to sow doubt in the reader’s mind.

I’m glad to know that’s my goal. I wasn’t aware of it until now. I’m more devious than I’d ever imagined! I had deceived myself into thinking that my goal was to display with clarity that Jesus’ words were altered by different Gospel writers to have different meanings. Now I see that really my goal was just to undermine people’s faith in the Bible. How much do I owe for this session?

Now to get a bit serious, Gantt has misrepresented me in each claim he’s made here. First, I do not show that inerrantists aren’t consistent in their interpretation of Matthew. I show that Matthew, Luke, and inerrantists (including Gantt), all disagree with each other about what this particular logion means. Second, I do not at all suggest that Jesus was “intentionally leaving out reference to ‘the Writings.’” I simply point out that he didn’t make reference to the writings. This is relevant because Jesus would have had issues with at least a couple of books in that corpus.

He never really establishes his case. He just keeps adding new charges. It’s like convicting someone in the court of public opinion by putting forth a never-ending barrage of accusations. After a while, people just assume the person’s guilty.

After reading Gantt, I’m no longer sure what case I was trying to make in the first place. My book must really be a mess.

That’s what Thom wants you to do: assume the Bible has errors. So there’s your choice: join Thom in assuming the Bible is characterized by errors or join Jesus in assuming the Bible is the word of God.

Amen! Follow me as you once followed Christ!

“It’s All About Me” – Here Thom acknowledges that Jesus says the Scriptures are about Himself, but then suggests what he’s going to declare boldly in chapter eight: that Jesus Himself was wrong. This is just a repetition of Thom’s fundamental thesis: the Bible is characterized by errors and Jesus Himself made errors. Take your pick of whom to believe about this: Thom or Jesus? At the end of this section, Thom repeats his unproven charge from an earlier chapter that Job and Ecclesiastes both deny the possibility of life after death and thus contradict Jesus. Just because these two books did not speak explicitly about resurrection in the same terms that Jesus did is hardly warrant for saying that a disagreement exists. Moreover, both imply resurrection even though the books don’t teach the concept explicitly, they do imply it.

Uh, no. Neither book implies it, and both explicitly deny it. Unproven? I’m sorry. Were the extensive direct quotations from both books denying the possibility of resurrection not sufficient proof for Gantt? I’d offer more evidence if I had it. Unfortunately, the direct textual evidence will have to suffice.

Unfortunately, Gantt here offers no commentary on the extensive discussion I provide about what it means for Jesus to be wrong, and whether that’s incompatible with his being sent from God. He offers no commentary on the context of the phrase, “It’s all about me,” and how Jesus’ reading of scripture fits within a larger apocalyptic Jewish hermeneutical framework we can generalize as pesher. None of the evidence or the arguments are relevant to Gantt. What it all comes down to is a choice between Thom or Jesus. If that’s what it really comes down to, then I say choose me, of course. But I’m not convinced that’s at all the choice before you, for the reasons I offer extensively in the book, which Gantt does not feel the itch to address.

“For the Purposes of Discussion” – Here Thom deals with Jesus’ statement that “Scripture cannot be broken.” He insists that Jesus wasn’t saying that Scripture couldn’t be broken – only that those who argued with Him believed that.

No. That’s not what I insist at all. My point is that you can’t base a doctrine on a conditional statement such as the one Jesus made here. Read it again, Gantt. Or save us both the trouble and don’t.

In other words, Thom believes Jesus was using the assumptions of His antagonists against them and not revealing His own view of Scripture. But Thom’s characterization just doesn’t hold up when you read the text. It’s clear that the “subordinate clause,” as Thom puts it,

Um, as grammar puts it.

is inserted by Jesus to make the very point that Scripture cannot be broken (even when it appears hard to believe). It would be redundant otherwise. This was a point therefore on which He and His antagonists agreed – and to use such points of agreement also a valid debating technique, and a more effective one at that.

Here’s another one of those unintelligible ones. “It would be redundant otherwise”? Huh? I’m going to have to side with myself on this one over against Gantt. And no, nowhere do I state that I “believe Jesus was using the assumptions of his antagonists against them.” I don’t state that’s my view. I don’t have a view on the subject. My point is simply that the evidence we have doesn’t allow us to form a rock-solid view about Jesus’ attitude to scripture. We can get a general picture. He treated it as authoritative. But what does that mean? Well, I think it means something very different for first-century Jews than it does for twenty-first-century evangelicals.

“A Spirit-Filled Proof Text” – Here Thom overlooks the fact that the belief of Jesus and His contemporaries was that the Holy Spirit was the inspiration of all the prophets who wrote the Hebrew Bible. Therefore, any mention of that name could evoke thoughts of future writing. It’s certainly not out of the question as Thom suggests.

Another strawman. I don’t “suggest” or otherwise state that such a reading (of Luke 14:16 and 16:13) is “out of the question.” I show that the inerrantists’ reading of it is hardly necessitated by the texts. Gantt seems to think my aim is to prove definitively that Jesus didn’t hold a certain view of scripture. He seems to have lost a sense of context. The context in which I am writing is in conversation with the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, a document which evangelical bigwigs use to beat other wannabe evangelicals into submission. They derive ironclad doctrines from texts which yield multiple readings, and demand allegiance to their reading if you want to join their “orthodox” club. If you don’t accept their readings, they’ll disparage you publicly or fire you from your position at whatever evangelical institution. Context is king, Gantt.

Thom then makes the unsupported and misleading claim that “much of the New Testament was not written by the apostles.” On the contrary, apostolic origin is the essential requirement for including a book in the New Testament. We have 27 such books, and the reason we don’t have more is that no one could be sure that any others were genuinely apostolic.

Yeah, my claim is unsupported, except for all the footnotes and arguments I provide throughout my book about authorship. But Gantt can’t even get my quote right. I didn’t say much of the NT wasn’t written by “the apostles.” I said it wasn’t written by “these apostles,” i.e., the twelve, i.e., to whom the promise in Luke is made. Come on, Gantt. You can’t even accurately portray minor points in my book.

“Literary Allusions” – In this section Thom says that just because Jesus referred to incidents from the Old Testament does not mean He was saying that they were without error. But, as I’ve been saying, Jesus believed the Old Testament was the word of God – to additionally say it’s without error would be superfluous.

Uh, no. That’s not what I said. I said that Jesus wasn’t interested in whether they had errors in them, and wouldn’t have to have that interest in order to make use of stories for one’s purposes. Read the damn arguments please, Mike. I also said that in all likelihood, Jesus’ view of scripture was pretty much the view shared by most conservative Jews in Palestine in the first century.

“The Heresy of Inerrancy” – In this section Thom argues with inerrantists about whether Jesus was omniscient during His earthly life. Although I don’t buy all that Thom says, I do believe that Jesus indeed grew in wisdom and knowledge and therefore was not omniscient when He was twelve years old. Nor do I believe He was ever omniscient in His earthly life. He was divine, but not omniscient. He gave up omniscience to become human. But He regained it in the glories after His resurrection.

So on what grounds does Gantt insist that Jesus must have been right about the infallibility of scripture? I don’t get it. If Jesus learned just like everyone else, and didn’t know everything, then it’s perfectly reasonable to assume that he held the views he was taught about scripture. Does that mean he held those views because he was divine, or because he was human? Well, the latter is the most we can say, if we accept that Jesus was not omniscient during his earthly life. Let’s put some real thought into this, shall we?

What’s clear is that Thom doesn’t want his readers to grow up to be inerrantists, fundamentalists, conservative Christians, or anything of the kind. He wants you to believe the Bible has errors. That’s very important to him. It’s a point at which he hammers and hammers and hammers.

Sorry, I should have talked about something else in my book-length criticism of the doctrine of inerrancy. And yes, I want you to believe the Bible has errors. That’s my end game. I want to undermine your confidence in the Bible. Regardless of what else I say about scripture, and its integral and positive role in Christian communities, what I really want is just for you to lose your faith in it.

By contrast, I want you to grow up to be like Jesus.

Whereas I want you to grow up to be like Nero, or Satan I guess.

And that begins with regarding the Bible as the word of God, just as Jesus did. If it’s the word of God, of course, it is without error.

A philosophical assumption that comes under direct attack in my book, an attack of course which is not featured in Gantt’s review.

Relevant to this point, Thom closes this chapter with an argument that if you think of the Bible the way Jesus does you’ll stunt your spiritual growth.

A mischaracterization. I don’t say, “If you think of the Bible the way Jesus does.” Those are Gantt’s words. On the contrary, my view is that Jesus argued with some of the authors of the Bible. He took positions contrary to theirs. That’s, for instance, what the whole “man born blind” episode is about.

Of course, such a view is ridiculous on its face. He’s saying you’ll stunt your spiritual growth if you imitate Jesus.

Now Gantt is just lying. I don’t say that, or imply that. He’s caricaturing my argument, and then presenting the conclusion of the caricature. On the contrary, my view is that if you imitate Jesus, you’ll grow spiritually and morally. Imitate him by arguing both from and with the scriptures. That’s how we grow. My view of Gantt is that he has to lie to win an argument (that I wasn’t even having with him).

But leaving that illogical thought aside

Well, even Gantt’s false claim isn’t “illogical.” It’s perfectly logical for imitation of Jesus to result in spiritual retardation, if Jesus was himself a spiritual retard. But neither Gantt nor I think Jesus was a spiritual retard. So that should be irrelevant.

let’s focus on this sentence of Thom’s: ”An infallible set of scriptures is ultimately just a shortcut through our moral and spiritual development.” (By the way, Thom writes these kinds of sentences a lot. They only make sense to those who read them superficially.

Or rather, they don’t make sense to Mike Gantt, for reasons about which I’m not going to speculate.

They don’t stand up to any reasonable scrutiny. Watch, and you’ll see what I mean.) Jesus accepted the Scriptures as the word of God and it did not stunt His growth. Nor was it a shortcut for Him. If it was, He would never have had to pray. But Jesus did have to pray. And He had to suffer. And “He learned obedience from the things He suffered.” He didn’t learn merely from the things He read. The Bible in no way answers every question you have to face in life. The Bible teaches you precepts and teaches you about God. It teaches you how to go to Him and wrestle over your moral choices. Jesus Himself was wrestling strenuously in prayer at the end of His life in the garden of Gethsemane. His acceptance of the Bible as the word of God was not a shortcut to the moral life. Rather it was an indispensable guidepost to that moral life. Since God is true He cannot contradict Himself. And since He cannot contradict Himself you can use the Scriptures as a point of comparison for the word of God you receive from any other source. If you do not believe that God speaks, you will be handicapped in all attempts at spiritual growth – for how else would you ever have a means of calibrating your own conscience?

The reason my statements (such as “an infallible set of scriptures is ultimately just a shortcut through our moral and spiritual development”) don’t stand up to Gantt’s scrutiny is twofold: (1) Gantt’s scrutiny isn’t “reasonable” and (2) Gantt isn’t scrutinizing my actual arguments, just sentences of mine he lifts and then invests with his own meanings. Of course we all agree that the Bible doesn’t answer every question we might be faced with. That’s not the point. The point is that some of the answers the Bible does provide will stunt your moral growth, if, that is, you’re committed to the Bible’s inerrancy.

You don’t need to critique the Bible. You need to let the Bible critique you. And if you allow this, your prayers will have more power and your life will have more substance in the sight of God. Thom doubts much of what he reads in the Bible, and he wants you to doubt it, too. Jesus wants you to believe the word of God…and do it.

You heard it here, er, umpteenth, folks.

RESPONSE TO GANTT’S REVIEW OF CHAPTER FOUR

What I do care about is the harm Thom does to those humble souls who read the Bible seeking to learn about Jesus Christ. He does this harm by trying to convince them that the Bible is not a trustworthy source.

And what I care about is the harm that inerrancy does to those same humble souls. And I do not try to convince anyone that the Bible is not a trustworthy source, just that it’s not a completely trustworthy source. Like everything else in life, we’re going to have to use critical thinking to find good guidance from the Bible.

My position is that Jesus is the revelation of God, and that the Bible gives a trustworthy and comprehensive account of His reality.

Is this a position piece, or a review? I’m confused.

To believe that the Bible is, as Thom says, “…fallible (and fallible in significant ways)” is to put readers of the Bible in an untenable position. Either they have to wonder whether the page they are reading is one of the reliable ones or else they are forced to rely on Thom, or someone else, to tell them which parts of the Bible are reliable.

Or, as Thom argues, we are all forced to rely on the same sources we always rely on when it comes to issues to which the Bible doesn’t speak. The Bible is a good source of insight, but it can’t be our only source of insight, because it’s also often a bad source of insight. It’s only fundamentalists who become paralyzed wondering “which page” they can trust and which they can’t. But spiritually mature people don’t seem to have that fear when reading the Bible.

And at the rate Thom is going, there won’t be many reliable parts left. It’s as if he’s snipping so many parts of the Bible away that he’s transforming it from a holy book to a holey book.

Hardy-har. Good one, Mike. Of course, in reality, I think (and argue) that the Bible is a tremendously useful source for moral insight. But fundamentalists like Mike need it to be all or nothing to make any use of it.

God – as well as His prophets and apostles – went to a lot of trouble that we might have the Scriptures. They did not do so in order that readers of the Bible might be uncertain of its veracity or dependent on other humans for its meaning.

Thom lays out scholarly findings for the lay person, but he’s only giving one side of the scholarly story. There are conservative scholars, just as committed to the tenets of academia as Thom is, who offer research which contradicts Thom’s conclusions.

And we’re stating the obvious because? Oh, right. Because for the fundamentalist, any scholar who says something to confirm the fundamentalist’s bias is right.

Most people don’t have time to explore both sides of the scholarly story to be able to draw their own conclusions. Thom is like the first-year medical student who can impress everyone at the party with his immense vocabulary. If he chooses to argue a medical point, who can argue with him but second-year medical students and above? Therefore, he pounds his reader into submission like a bully on an unsupervised playground pounds away at a smaller kid.

Not to mix metaphors.

I am pointing out, however, that Jesus Himself is supervising this playground. Jesus does not require you to have a graduate degree in biblical studies to read the Bible to profit anymore than He required it of His apostles. The best way to understand the word of God is not to approach it academically but rather to approach it practically. Consider it not in the context of a class or degree, but in the context of your life. Read it with a view to do it. He who does the word of God is the one who comes to understand it as God intended.

So said Joshua at the threshold of the Promised Land.

To characterize the source of most of our knowledge about Jesus Christ as wrong on many points, and important points at that, is to poison a well that quenches thirst for righteousness. May God forgive Thom, for surely he knows not what he does.

While I’m grateful for Mike’s forgiving spirit, I am obliged to reject the offer, on the grounds I haven’t sinned. Despite what Gantt would have you believe, the findings presented in my book are some of the ongoing results of my search for righteousness. That Gantt feels the need to characterize my work as poisonous says more to us about Gantt than it does about me.

Thom’s erudition (and he is no mean scholar) is on full display in this chapter. He plunges into water way over the heads of all but seminary graduates and tells a story of how the Bible is not so much breathed by God as it is a product of its geography and times. His is an old argument, well-known to seminary professors at both liberal and conservative seminaries. The former view it as accepted dogma, the latter view it as age-old heresy.

No, and no. See, in seminaries that promote critical thinking, very little is “accepted as dogma.” And I suppose the heresy is only age-old if by “age” Gantt means, the last hundred years or so.

Now you could go to a seminary library and find the conservative counter-arguments to Thom’s – but is that the way you want to live your life? That is, do you want to have to go to the bookstore or library to find a response every time you read book like Thom’s? This approach can consume a lifetime.

Well, I suppose if you’re going to base your life on the belief that the Bible is reliable, then yes, some investigation into the issues would be a good idea.

Authors like Thom and Bart Erhman can throw mud at the wall faster than anyone can clean it off.

I think Ehrman and I feel it’s the opposite. Fundamentalists can write ill-informed, biased and sloppy apologetics books faster than we can refute them.

For example, there are a group of conservative theologians who have put up a web site called the Ehrman Project to counter the liberal views popularized by Bart Ehrman. But Ehrman’s works are distributed by a large publishing house and reaches far more people than their little web site can reach.

Those poor souls.

It is not unprecedented for Jesus to find Himself surrounded by more accusers than defenders. Therefore, we must always remember that truth is not determined by the number of people who proclaim it.

Which is why I often feel alone when I’m defending Jesus against those who ignorantly dismiss him as an insignificant fanatic or a hate-monger.

At the end of the day, even if you could find and digest all the counter arguments to Thom and Bart, you’d still be stuck with an unpleasant choice: which set of experts to believe?

Generally, I would recommend believing the ones who make the better arguments, further information pending.

They both are trained in matters at which you can only guess. It’s like having to choose between two heart surgeons debating about medical techniques of suturing – you know it’s important, but you lack the vocabulary and skill to decide between them. In the end, you have to rely on your gut. Why not rely on your gut to start with – which in this case is more precisely your conscience – and choose the Man from Galilee to be the one who operates on your heart? Leave the bickering surgeons to themselves.

In short, give your allegiance to truthiness.

I do not object to all the observations Thom makes in this chapter. It’s the conclusion to which he leaps that I object. For him, a survey of ancient Near Eastern literature and a full embrace of liberal orthodoxy about the origin of the Bible lead him full-speed ahead to the conclusion that Moses did not write the books that ancient Israel – including Jesus and His apostles – attributed to him.

A point which has, of course, very little to do with my argument in chapter four.

As for which Israelites did write those books, Thom is sure – with liberal orthodoxy supporting him – that the early authors were polytheists and the later editors and authors were monotheists. He can’t name them, but he knows for sure it wasn’t who the Bible says it was.

Ooh. Burn. Of course, the books of the Pentateuch make no claim whatsoever to Mosaic authorship. That’s later tradition. Again, there is no “Bible” that makes a claim about itself. There are only certain people who make certain claims about certain texts. As for my inability to name the authors of the Pentateuch, guilty as charged. I also can’t name all the authors of other ANE lore, but scholars don’t attribute them to their traditional authors either. I can’t name all of the authors of the Iliad, but Iliad scholars will give you ample reasons why Homer isn’t really one of them. All Mike’s comment here displays is his vast ignorance about how legendary origin texts were formed in the ancient world. He also displays his ignorance about anonymous and pseudonymous authorship in the ancient world. But really what you should take home from this is that, since I can’t give you the names and genealogies of the authors of the Pentateuch, I represent a really silly, pseudo-scholarly position.

Once again, you don’t have to have a graduate education in biblical studies to make your choice of whom to believe: Thom or Jesus.

That’s right. It all comes down to a choice between me or Jesus. All the weight of everything I write is on me and me alone. It’s just my credibility versus that of a two-thousand-year-old peasant who never wrote anything down. Clearly the choice is obvious. It’s a no-brainer. It’s me. Abandon your faith in Jesus and worship me. Not as a divine being. Just as someone with an intellect superior to yours. Take what I say on faith. Do as Mike Gantt tells you. Go with your gut. Don’t waste your time with books. Just believe in me, and my truth will set you free. I have come that you might have life, and have it more or less the way it already is.

And the choice is even simpler than that: Do you believe the words of the Savior brought you to by men who shed their blood in giving their testimony about Him or do you let yourself be pulled back and forth by the argument between errantists and inerrantists dwelling in academic ivory towers?

Ah yes, believe because the martyrs shed their blood to give you their testimony. Because only faithful Jews and Christians have ever shed their blood for their religion.

There’s no denying that polytheism marked the ancient world, just as there’s no denying that monotheism marks the modern world. That’s why some of Thom’s observations have value. However, these observations are framed in an argument from Thom that leads in only one direction: “You should not trust the Bible to be the word of God!” What good are his valid observations if you aren’t allowed to reach more productive conclusions with those observations?

A great point! What good are my observations if they’re not productive? That is to say, what good are my observations if they don’t confirm what you already believe, or what Mike Gantt already believes? The answer? They’re clearly good for nothing. I stand corrected. I hadn’t considered the utility of the facts, so lost was I in their factness.

Jesus Christ, through the coming of His kingdom, pulled the world out of polytheism into the monotheism that Abraham had championed so long before Him.

Yeah, no. Abraham was not a monotheist. He, like most other ancient Near Eastern peeps, was a monolatrist—a believer in multiple deities who worshiped only one.

In his chapter heading Thom asks “Whither Thou Goest, Polytheism?” The answer is “Into the oblivion of history…where the Champion Jesus Christ sent it.”

Should we be playing Carmen for this line? Anyway, Jesus had nothing to do with the dissolution of polytheism in Israelite religion. That happened several hundred years before he broke his mother’s hymen.

In short, Gantt doesn’t disagree with what I write in chapter four. He just doesn’t think we need to worry about it, because, well, just because.

RESPONSE TO GANTT’S REVIEW OF CHAPTER FIVE

Thom’s animus towards the Scriptures as a source of truth fully blossoms in this the fifth chapter: Making Yahweh Happy: Human Sacrifice in Ancient Israel.

Right. I hate the Bible! That’s why at the end of my book I encourage my readers to continue engaging it, and continue seeking words of life from its pages. That’s why I say that I love it. Because I hate it. I’m using reverse psychology, or something.

Thom’s goal throughout the book has been to destroy the Bible’s reputation for truth among a broader public.

Yes, that is my goal. Not to be honest. Not to share my struggle with the scriptures. Not to encourage others to struggle with them, as I lead on. No, my real goal (unspoken, because I’m a conniving wolf-in-sheep’s-clothing) was always to utterly destroy your faith and stake my claim on the rubble.

It seems to bother Thom greatly that the Bible has a reputation for representing the truth of God. Every aspect of his considerable intellect is brought to service in his goal of making that reputation appear completely undeserved. With each chapter of his book, Thom’s view of God becomes clearer and clearer to us – and it is a dim one. I pray for him.

I pray for this guy too. What’s his email address? I’ll send him a note of concern.

Thom seeks to get his readers to believe that child sacrifice was a normative part of ancient Israel’s worship of God. Underlying Thom’s analysis of the subject is his unwavering acceptance of the Documentary Hypothesis (also called J-E-P-D theory). Because he believes there are clandestine authors and editors of the Old Testament, and because he believes Jewish law evolved rather than being handed down through Moses at Mount Sinai, he manages to read a progression in Israel’s view of child sacrifice from favorable to unfavorable over centuries’ time. That is to say, Thom is offering this as another “example” of how the Bible contradicts itself.

“Clandestine authors.” That’s a good one. I’ve always thought of them as scribes under the employ of kings, but maybe Gantt has it correct.

As is Thom’s practice, he employs data that favors the conclusion he wants (that is, you can’t trust the Bible) and omits evidence that doesn’t. For example, in his discussion of Abraham’s uncompleted sacrifice of Isaac he neglects to mention that Hebrews 11:17-19 says Abraham believed that had the sacrifice been completed, God would have raised Isaac from the dead. In other words, Abraham only followed through on the sacrifice because he believed it would not result in the death of Isaac.

Right. Dammit. I should have mentioned the completely irrelevant witness of an interpretation of the text from about two thousand years after the period in question, a witness which speaks of Abraham’s belief in resurrection about 1600 years before such a belief came into existence. I am such a cherry-picker!

Thom also fails to explain why, according to Thom’s theory that child sacrifice was prevalent and approved, Abraham wouldn’t have jumped at the chance to sacrifice a child. Where’s the dilemma for Abraham if sacrifice of children is considered a good thing?

Oh, I see the problem. Gantt hasn’t read Genesis. Well, let me summarize. (I summarized this in the book also, but since Gantt isn’t familiar with Genesis, the details must have been lost on him.) Isaac was the child of promise. Hence Abraham’s conflict. Recommended reading: Genesis 11-22.

Of course, we know now that God orchestrated the entire Abraham-Isaac event to foreshadow the sacrifice of His own Son. The willingness of the son, the wood, the third day, are points in the outline of that shadow. Thom is not intent that his readers see Christ, however; he’s intent that his readers see the Scriptures as an altogether human document – with no divine hand involved.

Oh, that makes sense. I’d always read it as a foreshadowing of the sacrifice of Mesha’s son. But I guess Jesus is a good fit too, and probably works better in the broader context.

Next, Thom discusses Jephthah’s daughter, but he fails to mention that scholars disagree about the outcome of that sacrifice. That is, some scholars believe that the virgin was killed and others believe that she was denied the privilege of marriage (hence, “And she had no relations with a man”).

True. I fail to mention that there’s a fringe position that says, contrary to the text, that Jephthah didn’t actually sacrifice his daughter. I should have given it the serious space it deserved, like in a one sentence footnote. I love this phrase, “scholars disagree.” It’s a favorite phrase of apologists. Get a handful of scholars who hold one position against the vast consensus, and pretend that constitutes a lack of consensus. It’s a brilliant tactic. I’d use it myself if I had more nerve.

Even if she were actually killed by Jephthah, there is nothing in the text that indicates God approved – and there were many actions in the book of Judges of which He did not approve.

Yeah, nothing in the text indicating that God approved, except that the spirit of Yahweh was upon Jephthah, and the fact that after Jephthah made his deal with Yahweh, Yahweh kept up his end of the contract. See my extensive discussion of this in my review of Copan’s book, entitled, “Is God a Moral Compromiser?” available freely, well, on Google.

We have the outright condemnations of child sacrifice in the prophets, but Thom manages to find a way to reinterpret even these.

Right. “Thom” manages to find a way, by which Gantt must mean, “the scholarly consensus.” By “reinterpret” he must be referring to Micah 6, which in fact is not a condemnation of child sacrifice at all. It’s not called “reinterpretation.” It’s called “interpretation.” Or, as I prefer in cases like these, “reading.”

The ones that he can’t reinterpret are assigned a later date so that it fits his theory that what God used to enjoy, He later frowned upon.

Right. I “assign” Jeremiah and Ezekiel to a “later date.” They didn’t just happen to live in a much later time. I “assigned” their time periods to them in my omnipotence. We are currently existing in Alternate Universe 11638, which is a universe I created as I was writing my book. Previously, we all existed in AU11637, and in that universe, Jeremiah and Ezekiel were contemporaries of Moses.

A God who changes his mind – that’s the kind of God Thom’s book portrays. Or, perhaps, to put it more accurately, Thom’s book portrays a Bible produced by people whose conception of God changes over time

Yeah, the latter.

– as if God Himself wasn’t even involved.

No, go back a bit. You had it.

Am I being too hard on Thom? I hope not.

If only you would be! My sarcasm is spreading thin.

But I do hope I’m being very hard on his book because I believe it is toxic to sincere and humble faith – even to his own, if he has any left. This book constantly attacks faith in a good and loving God.

No, it attacks faith in a morally monstrous God. It actually advocates faith in a good and loving God.

Or as Thom himself put it, he’s against “someone who believes that everything the Bible affirms is true, and good, and that it comes from the mind of a kind, loving, merciful, and just God.”

Well, I’m against the belief, not really the person who believes it. And that’s very different from being against faith in a good and loving God. How shall I explain the difference so Gantt can get a grasp of it? On the one hand, we have faith in a good and loving God. I’m for that. On the other hand, we have faith that the Bible portrays a single God who is consistently always good and loving. I’m against that. I’m against the latter because it’s a false belief. I’m for the former because I hope it’s true, and because it promotes good and loving human behavior.

Thom did not invent the doctrine he teaches. He is simply passing on warmed-over anti-biblical academic dogma – though his presentation is stylishly geared for a popular audience.

So I’m a flashy used car salesman. Got it. By the way, what are you driving, Mike?

Greater condemnation belongs to those who originated so much of this kind of disinformation about the Bible that is published and cataloged in academia. There is nothing wrong with honest historical inquiry, but when that inquiry is systematically used to destroy faith in our Creator and Redeemer then it deserves strong condemnation.

I can get on board with that. As long as John Collins takes the brunt of the beating, I think my book royalties will be worth it.

Thom is not writing a scholarly book, he is writing a popular book that presents a certain scholarly view. Were he writing a scholarly book, he’d be forced to deal more honestly with those who oppose his position. He’d have to put forth their best arguments and then show how his were superior. Instead, Thom puts forth only the weakest of his opponents’ arguments – if any at all.

A claim without any substantiation. I picked the best arguments against my positions I could find. Perhaps it’s just that they look weak to Mike after I got through with them? I admit, N.T. Wright’s preterist reading of the Olivet Discourse looked pretty weak after I got through with it, but Gantt may be surprised to learn that Wright is actually a very reputable scholar whose arguments have been taken very seriously by mainstream scholarship and have persuaded many. As for human sacrifice, my chapter is adequately footnoted for a semi-popular volume, and any time a scholar (such as Richard Hess) has attempted to challenge my readings of the texts, I’ve not shirked back from exposing the insurmountable weaknesses in his “strong arguments.”

I don’t mind that Thom takes a position and seeks to have his reader accept it. I do the same thing myself in my blogs. The difference is that I am trying to build something (faith in Christ) while Thom is trying to destroy it.

Yep. That’s the difference. I’ve already admitted to this. I just want to stake my claim on all the piles of rubble that were once the faith of the faithful. That really is the key difference between Mike and me. Why would I want to build anything anyway? That wouldn’t be consistent with my goal, which is to steal and destroy. All I really want to do is make money off of book sales, and I know that the easiest way to sell a lot of books is to write a book for Christians that tells them everything they don’t want to hear and undermines the very foundation of their existence. Those books sell like hotcakes, which is why I chose to get in on the action myself.

I do not ascribe evil motives to Thom in this regard. He is attempting to destroy belief that the Bible is the word of God because he thinks such a belief is bad for you.

Oh, I’ve divulged too much then. I guess all those times Mike complained about the fact that I charge money for my book while his book is available online for free wasn’t about ascribing evil motives to me either. Good then.

Therefore, both he and I are trying to do what we believe is in your best interest. You, however, will have to decide between our views. I am making the choice clear. I am saying that the Bible is a true and completely reliable witness to the reality of Jesus Christ, our Creator and Redeemer. Further, I am saying that Jesus Christ Himself is the truth – the “pearl of great price” – to which the Bible testifies.

Thom has promised that in the final two chapters of his book he will provide “reading strategies” for the Bible. I look forward to hearing what he has to say in that regard, because so far I can’t see why anyone would want to read a book that he has described as unreliable, which portrays a God he describes as reprehensible (promoting child sacrifice in this chapter, genocide in the next).

Oh, I can help with that. I think it’s because we can learn valuable things even from books that contain bad content. Like an N.T. Wright monograph, or an Anne Rice book (not necessarily the vampire bits, more the prose bits). Especially when those books are actually a collection of books with multiple authors who have different and interesting views on a number of subjects! Those books are very rewarding, spiritually, morally, intellectually, and otherwise, and I happen to think the Bible is the best of the bunch! On the other hand, Mike says it’s all or nothing. So that, I would propose, is really the choice readers have to face. Not between Thom and Jesus (although who you ought to choose in that case is unarguably clear), but between a four-year-old, all-or-nothing, tantrum-thrower’s approach to the Bible, and a mature, realistic, and nuanced one. And I’ll admit, while reading the Bible sometimes makes me want to throw a tantrum, I advocate for the latter approach. It’s better for everybody really.

Before I close this post I should mention how Thom deals with the outright denunciation of child sacrifice made by Jeremiah on behalf of God in Jeremiah 19:5-6. Here’s an excerpt:

“…Jeremiah has Yahweh saying that he ‘did not command or decree’ the practice of sacrificing children to Baal, that such a thing ‘never entered my mind.’ But this strains against credulity.”

It may “strain against credulity” for Thom, but not for anyone who has more faith in Christ than Thom does – or for anyone who has more faith in Christ than they do in Thom.

Right, because that’s what it’s about—how much faith in Christ you have. It’s not about hermeneutics or texts; it’s about the measure of your faith. Remember that, folks, the next time you’re talking with a Mormon about The Pearl of Great Price, or a Muslim about the Qur’an.