Response to Denny Burk Review

[Cross-posted from Religion at the Margins]

Another Attempt To Discredit My Book Discredits Itself

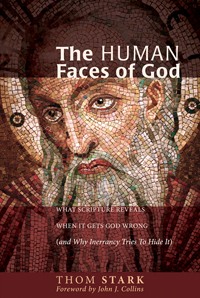

Denny Burk, Associate Professor of Biblical Studies at Boyce College (of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary), has published a review of my book, The Human Faces of God, in the Southern Baptist Journal of Theology. (For a previous engagement of mine with Burk, see here.) On his blog, his review is entitled, “Another Attempt To Discredit Inerrancy Falls Flat.” In the review, Burk attempts to argue that my book fails in both of its objectives: (1) to discredit the doctrine of inerrancy on a number of grounds, and (2) to provide an alternative way of reading the Bible as Scripture that isn’t confined by the artificial strictures of Christian fundamentalism (these are my words, obviously not Burk’s). But in order to make his case that I have failed on both points, Burk is forced blatantly to mischaracterize my arguments and positions at almost every turn. I hardly recognized the book he was reviewing.

Now, in a number of places, I will willingly chalk up Burk’s mischaracterizations either to sloppy reading habits or to a simple inability to understand my position due to an inability to see these issues from a paradigm other than his own fundamentalist paradigm. Indeed, Burk can only claim that I have failed to provide an alternative to fundamentalism because in order to understand that alternative paradigm, one must first have a paradigm shift. As I stated clearly in the preface to my book, I do not expect my arguments to induce such a paradigm shift among the most devout adherents to fundamentalism. This is not because my arguments are deficient, but because I know from decades of experience in the world of fundamentalism (including years within that world where I myself was no longer a fundamentalist) how powerful the anti-intellectual grip is that fundamentalism tends to have on otherwise very intelligent people.

That said, there are certain points in Burk’s review where it is very hard for me to believe that his mischaracterizations are unintentional. Not infrequently, Burk has taken to changing the wording of my own positions in such a way as to give his summaries of my positions a very different meaning than my actual positions themselves. In one case, Burk deliberately changed the wording of a quote of mine, which had the effect of giving my authentic words almost the opposite meaning. I want to give Burk the benefit of the doubt and say that he didn’t do this intentionally, but if it wasn’t intentional, the best I can offer is that Burk must be incredibly dense. So, I’m put in a position where giving him the benefit of the doubt isn’t really an act of charity on my part. I just see no way to be charitable, as much as I would like to be.

Burk begins his review by comparing my book to the books of Bart Ehrman, which ordinarily I wouldn’t have a problem with, even though I find myself in disagreement with Ehrman almost as often as I find myself in agreement with him. Burk says that my book belongs to “the Ehrman-genre,” though he notes that unlike Ehrman, I wish to preserve the whole Bible as scripture. This latter clarification is one of the few accurate statements made in Burk’s review. But he’ll undo it almost immediately. The problem I find, however, with Burk’s comparison of my work to Ehrman’s is not found in anything he explicitly says, but in the implicit import of the comparison: to Burk’s audience, as he well knows, Ehrman is anathema. And so, Burk is playing a little guilt-by-association game. He’s informing his fundamentalist audience that they have permission to categorize me as “another Ehrman,” which when translated means, “anathema.” The end result is fine I suppose. My position should be as much anathema to fundamentalism as fundamentalism is anathema to me. I just would rather Burk bring his audience to that conclusion after a careful consideration of my arguments (to which we are never treated) or at least an accurate summary of my positions (which we don’t get either), rather than shortcutting the process by painting a scarlet “E” on my forehead at the outset. But don’t hear me playing the victim. I really don’t expect much better from most fundamentalist apologists, and I’m not wounded in the slightest by such tactics. I just point it out to make clear what kind of a “book review” it is that we’re dealing with here. And all that aside, come on. Ehrman did not invent this genre. There’s a long tradition of such books going back long before Ehrman came on the scene, and I’ve read more of those books than I have of Ehrman’s. Apparently Burk has not.

Another thing Burk points out here is that I am, like Ehrman, a former fundamentalist, as I state also in my preface. Again, Burk points this out because, implicitly to his audience, this means that I am doing what I am doing because I am disgruntled and disillusioned. Burk is stating the fact of my former fundamentalism in order to afford his audience the opportunity to make the standard armchair psychoanalysis that fundamentalists use as a defense mechanism against scholars like Ehrman. Of course, what Burk doesn’t know, because he doesn’t really know my story at all, is that between my fundamentalist years and the time I wrote Human Faces, there were about five or six years in which I was neither a fundamentalist nor what Burk would characterize as a “liberal.” I was what’s called a postliberal Christian, Wittgensteinian to be precise, on the model of such Calvinists as D.Z. Phillips and Rush Rhees, or such Lutherans as George Lindbeck. Of course, to a fundamentalist like Burk, it must be hard to tell the difference between Lindbeck and, say, Ehrman, or, say, Satan. But just because a fundamentalist can’t see the distinction doesn’t mean there isn’t a world of difference. And I was a Wittgensteinian postliberal Christian when I began the work that became Human Faces, and in many, many ways, I still am. Of course, in many ways I no longer am, but that’s actually what Human Faces is about for me, as I also stated in the preface. It wasn’t just aimed at fundamentalists or those struggling on the fringes of fundamentalism, but also at my postliberal kin, because I wanted to make it clear why postliberal hermeneutics does not have all the answers for all the problems inherent in Scripture either. So as much as Burk might like his readers to think that I’m yet another disgruntled “former employee” (as I would characterize Ehrman in some of his early books), the reality is that I wasn’t writing from an anti-fundemtnalist paradigm, but from a postliberal paradigm, even as I was forced to move beyond that postliberal paradigm in significant ways.

The second paragraph of Burk’s review consists of another attempt to implicitly discredit my book, by pointing out that the arguments in my book don’t offer anything new to scholarly debates. Burk can mask his motivation in pointing this out by quoting me saying as much in my preface. Burk can pretend he’s simply describing my book as I myself have described it, but he knows that by doing so, he’s providing another reason for his audience not to take my arguments seriously. He characterizes the arguments in my book in his own words as “well-worn,” which obviously has a useful double connotation. It can simply mean, “old,” “tried and tested,” or, as the dictionary defines the term, “repeated too often; trite or hackneyed.” So it’s clear that Burk is bringing this fact up not really to be neutrally descriptive of the content in my book, but rather in order to discredit the same, under cover of a convenient quote from the author himself.

But I have two things to say in response to this. First, while I did say that it wasn’t my goal to offer new hypotheses or material to scholarly discussions (but rather to make the discussions available to a non-scholarly audience), I was being a bit modest. The truth is there are important arguments that I make in Human Faces of God that I think are original contributions to scholarship. Burk no doubt did not identify them when he read the book, and I won’t guess as to why he failed to do so.

Second, see, from my perspective (and I do believe that my perspective is really quite sane here), writing a scholarly book that doesn’t offer radical new hypotheses is a good thing. In scholarship, at least as I was trained by Christopher Rollston, “new” is often a euphemism for “irresponsible.” That’s not to say that advances aren’t made in scholarship, and that new hypotheses aren’t essential to coming to a consensus. It’s just to say that most of scholarship consists of restating what’s already been said but with different details in different contexts. While every generation or so in a given field, some groundbreaking work will be done by one or two scholars, in every generation, most of the scholars who attempt to do groundbreaking work find themselves suddenly on the fringes of the academic community. (#coughtabor.) So from my point of view, taking the consensus, and restating it, either for new audiences, or in the context of a new question, is the meat and potatoes of scholarship (forgive the metaphor, vegans). It’s what most scholars do with themselves, most of the damn time. And I most certainly wasn’t going to be caught dead doing anything else with my first book. It’s called being sane.

Thus, the fact that I am articulating consensus positions in a popular voice (and in a clearer way, in some cases, than I think has been done before), does not mean that my arguments are “well-worn,” as in “hackneyed” or “outdated.” It means, rather, that the scholarly consensus, for the most part, stands firmly behind me as I make my case. In any other world but the world of fundamentalism, that’s rather a good thing.

Now, Burk’s first distortion is rather mild and may just be a case of a bad grammatical choice, but it’s a distortion that is repeated several times subsequently, so while I can give him a pass here, I won’t be able to do so later. Burk writes, “Stark hopes his book will speak to Christians who struggle with biblical inerrancy and who have not found answers to their questions about the Bible. Stark wants them to know an ‘alternative way of being Christian’—a way that vehemently rejects the Bible as inerrant (xviii).”

I do not in fact “reject the Bible as inerrant.” Rather, I reject the inerrancy of the Bible, while embracing the Bible in its entirety, in various different ways, as Burk knows, but will obfuscate later. He should not have said, “vehemently rejects the Bible…” but rather, “vehemently rejects the doctrine of inerrancy.”

Now immediately on to other distortions. Burk writes, “Chapter one contends that the Bible is ‘an argument against itself’ and is hopelessly self-contradictory (1).” Burk here actually changes my vocabulary inside a supposed quote. I do not say that the Bible is an argument against itself. I say that the Bible is an argument with itself. That may appear a minor distinction, but the implications are significant. “Against” itself has a much more negative connotation. “With” itself was my choice of words precisely because I am, with John Collins, characterizing the debate that takes place within the pages of the Bible as a healthy thing. If I had actually said that the Bible was an argument against itself, my meaning would have been that the Bible nullifies itself, which I do not believe. Moreover, “hopelessly self-contradictory” is again Burk’s choice of words, not mine, and mischaracterizes the portrait I am painting. I think Burk’s mischaracterizations here are probably just due to his inability to understand my actual position; an inability to come around to seeing that a Bible with contradictions can actually be a good thing. That I think it is a good thing is abundantly clear in a number of places throughout Human Faces. It’s clear in my approving quote of John Collins at the beginning of chapter 1, where Collins says that the Bible is a “collection of writings that is marked by lively internal debate and a remarkable spirit of self-criticism.” See. That’s a good thing. Again at the end of chapter three, I argue that the Bible is not the problem; the problem rather is the artificial construct of inerrancy and the limitations it imposes upon us as moral agents. The solution is to go back to a more ancient way of engaging the biblical texts, which is the form of engagement modeled within the texts themselves, that is, one of engaging in an ongoing argument, with ourselves, and with certain biblical texts. The Bible doesn’t present us a single point of view, but offers us options, and encourages us to struggle to find God in the mix. To engage in that argument with the text, from my perspective, is to participate in the oldest of biblical hermeneutical traditions. And it is the process of the struggle and the argument itself that makes us into properly moral agents. That this is my perspective is abundantly clear, but it is a perspective that becomes distorted in Burk’s fundamentalistic recasting of my argument.

Burk continues to summarize chapters two through ten in one-sentence each. They are more or less accurate, with the exceptions of his descriptions of chapters five and six. Burk writes, “Chapter five attempts to demonstrate the moral inferiority of the Bible by showing that the authors believed in the ‘nobility and efficacy of human sacrifice’ (99).” This is a fairly obvious distortion that Burk could have easily avoided by adding the qualifier “some of” before “the authors,” but this is a distortion that Burk produces consistently throughout his review, as he continually fails to acknowledge that I see different perspectives at work in the Bible. Without fail, he characterizes my criticisms or descriptions of some biblical authors as criticisms or descriptions of “the authors” of the Bible, or simply, “the Bible.” This creates a serious misunderstanding and the primary point of a book review is to inform people who have not read a book about its contents. Anybody who has not read my book will come away from Burk’s review with a very distorted picture of the very clear and consistent view of Scripture that I articulate from the first page to the last. And anybody who has read my book will know that Burk’s review distorts my view. This is unfortunate. For instance, there’s no way that Burk could have even skimmed my chapter on human sacrifice in the Bible without realizing that I argue that the voices that see human sacrifice to Yahweh as noble are earlier voices that were drowned out by later voices from the seventh century on, and it is these voices which became the orthodox ones on the issue. But Burk’s review will lead the reader to believe that I argue that “the authors of the Bible” think that human sacrifice is noble, which makes me sound like a nutcase, which of course works well to Burk’s advantage. Go figure.

And his one-sentence summary of chapter six, while not technically inaccurate, is a bit misleading: “Chapter six highlights ‘Yahweh’s Genocides’ in the Old Testament and concludes that God never commanded such things as the conquest of Canaan.” While it’s true that this is what I conclude, Burk’s description may easily lead the reader to think that my conclusion is based upon a textual argument. But it is not. Rather, it is based upon a moral argument, and on the working assumption that the true God is a moral God. In other words, if the genocides cannot be morally justified (as I extensively argued in one of the longest chapters in the book), and if God is unswervingly moral, then it is not very likely that these genocidal commands came from God. I believe that they did not, because of these two premises, and not because of any textual argument.

From here on out, Burk’s deceptive and distorted statements begin coming in full force, one after the other. As I said at the outset, I would chalk these up to a simple inability on Burk’s part to comprehend a paradigm different than his own, were the distortions not so blatant and, indeed, deliberate. It is almost as if Burk feels he needs to rewrite my book in order to make it easier to dismiss. But certainly an accurate summary, and criticisms of my actual positions, would be more useful and still well-received by his fundamentalist target audience. I just see no justification for Burk’s maneuvers, not even a pragmatic justification. What this displays to me is the profound cynicism embedded into the fundamentalist worldview.

After his single-sentence summaries of my chapters, Burk launches into an attack on a flagrantly straw-man version of my concluding chapter. He writes:

“It is in this final chapter that the futility of Stark’s quest comes into full view. After nine chapters of attacking the historical, theological, and moral authority of the Bible, he thinks he can offer a way of reading the Bible that will preserve it as Christian Scripture for the church. Since the biblical text taken on its own terms has an ‘evil,’ ‘devilish nature’ that reveals God to be a ‘genocidal dictator’ (218, 219), Stark argues that the only way to read the Bible faithfully is to read it as ‘condemned texts.’”

The distortion here is flagrant. Burk describes me as arguing that “the biblical text” (singular!) has an “evil,” “devilish nature,” that reveals God to be a “genocidal dictator.” He has the nerve to claim that my proposition is to read “the Bible” (singular!) as “condemned texts.” Not only is this utterly deceptive, it is profoundly cynical. As Burk (and anyone who skims my book) well knows, I argue that some texts in the Bible depict God in “evil” and “devilish” ways. At the same time, I show that other texts dissent from these portraits of God and portray God in a morally consistent way. It’s in the very title of my book, The Human Faces (plural!) of God. There is not, on my view, any “God of Scripture.” There are different depictions of God, by different authors in the Bible, and not all of them are in agreement with one another. I argue this from chapter one to the very end. Burk could not have missed it; instead, he opts to utterly hide this fact from his audience. Even when he summarizes my characterization of the Bible as an argument, as we noted, he mischaracterizes this as an “argument against itself.” The reader of Burk’s review has no way of knowing what the very premise of my book is.

And Burk picks up my strong language, again in an effort to discredit me in the eyes of the pious evangelicals. Stark called God evil? Devilish? Anathema! But of course, I did not call God evil or devilish. I argued that there are some wonderful depictions of God in the Bible, and some morally deficient depictions of God in the Bible, and I gave argument after argument in order to support my conclusion that some of these depictions of God are morally deficient. It’s not a conclusion I came to lightly. But the Stark of Burk’s fictional world is a God-hater. In reality, of course, I stand in a long tradition, going back to many of the biblical authors themselves, of believers who in their zeal to honor God have in no uncertain terms rejected deficient depictions of God. I even cited prominent orthodox figures from church history in whose tradition on this I stand.

For instance, I quoted at length from Gregory of Nyssa, one of the Cappadocian Fathers, one of the chief architects of the doctrine of the Trinity, and a thoroughly orthodox theologian by any current standard bearing the name. Gregory found a huge moral problem with the tenth plague (the slaughter of Egypt’s firstborn children). In his Life of Moses, Gregory asks, “How would a concept worthy of God be preserved in the description of what happened if one looked only to the history? The Egyptian (Pharaoh) acts unjustly, and in his place is punished his newborn child, who in his infancy cannot discern what is good and what is not. His life has no experience of evil, for infancy is not capable of passion. He does not know to distinguish between his right and his left. The infant lifts his eyes only to his mother’s nipple, and tears are the sole perceptible sign of his sadness. And if he obtains anything which his nature desires, he signifies pleasure by smiling. If such a one now pays the penalty of his father’s wickedness, where is justice? Where is piety? Where is holiness? Where is Ezekiel, who cries: The man who has sinned is the man who must die and a son is not to suffer for the sins of his father? How can the history so contradict reason? (Mos. 2.91)”

Gregory argues that if we are to understand the tenth plague as actual history, then God would have been a perpetrator of a gross injustice. He states in no uncertain terms that there is no holiness in the slaughter of the firstborn, no piety, no justice. He emphatically avers that such a plague would be contrary to moral reason itself. To put it in contemporary terminology, Gregory is arguing that if the tenth plague is historical, and God actually killed the firstborn of Egypt, then God is a moral monster. So much for Burk’s insinuation that I’m a God-hater who comes to the conclusions I come to because I’m disgruntled. Rather, it is my zeal for God that compels me to condemn certain (but certainly not all) texts in the Bible as immoral depictions of God, in Gregory’s words, depictions not “worthy of God.”

Gregory’s solution, of course, is to opt for an allegorical reading of this passage, because morality demands that we reject a historical reading. And as I state clearly in my book, while I am sympathetic with Gregory’s approach and appreciate its intent, I ultimately believe that allegorical readings don’t solve the problem; they just sweep the problem under the rug by changing the subject. That’s not to say that I think we should never use allegory, but my position, as I argue in the book that Burk didn’t review, is that we must first have confrontational readings, much as Gregory’s confrontation with the tenth plague text.—As I stated clearly in the book, it’s not that allegorical readings are a problem in and of themselves (except for the Chicago inerrantists who insist on a historical-grammatical reading). Allegorists like Origen and Gregory consciously chose allegorical readings for texts where the biblical morality could not be salvaged. The problem with them is that over time, this original moral consciousness is lost on subsequent generations, and only the allegories remain, which has the effect of sweeping the moral problems under the rug.—Moreover, just as I do, Gregory used scripture against scripture. He cited Ezekiel favorably in order to condemn a historical reading of the passage in Exodus. And Gregory’s position is mine as well. The Bible has different perspectives, and we can be enlightened enough by the good perspectives in order to identify and confront the bad ones, just as Gregory and so many others of our forebears have done before us.

But according to Burk, I argue that “the Bible” is a condemned text, and that “the God of Scripture” is devilish. This is a monumental deception, and if you’re not convinced that Burk is being deceptive (maybe he’s just being dense), then let’s proceed to his very next sentence:

“It will be useful to read Stark’s prescribed hermeneutic in his own words: ‘[The Bible] must be read as scripture, precisely as condemned texts. Their status as condemned is exactly their scriptural value. That they are condemned is what they reveal to us about God. The texts themselves depict God as a genocidal dictator, as a craver of blood. But we must condemn them in our engagement with them’ (218).”

The comic irony here is that while Burk claims to be offering “Stark’s . . . own words,” Burk deliberately changes my words and gives them a radically different meaning. So much for my “own words” being “useful.” Burk quotes me: “[The Bible] must be read as scripture, precisely as condemned texts.” And he inserts his own words (“The Bible”) into brackets in place of my actual word. My actual word was “they” (plural, not singular) and “they” referred to certain biblical texts, like the text that Gregory rejected on moral grounds. “They” emphatically did not refer to “the Bible” as a whole, but for some reason, this is the narrative that Burk wants to spin, and he goes so far as to deliberately change my words in a direct quote in order to spin this narrative. I’ll quote the preceding portion of this section of my book in order to make it clear to any interested parties what I was really saying:

The question looms: what are we to do with those texts we find ourselves wanting to condemn? While the scriptures advocate monotheism, the dissolution of the sacrificial system, and the love of enemy, they also advocate a polytheistic tribalism, human sacrifice, and religiously motivated genocide, among other deplorable things. What should our strategy for dealing with these damnable texts be? Should we simply ignore them? Excise them from our canon? The only honest answer to the question I have been able to come up with is this: they must be retained as scripture, precisely as condemned texts. Their status as condemned is exactly their scriptural value. That they are condemned is what they reveal to us about God. The texts themselves depict God as a genocidal dictator, as a craver of blood. But we must condemn them in our engagement with them—sometimes with guidance from other passages of scripture, sometimes without. That they stand as condemned is what they mean for us as scripture. (217-18)

Burk can reject this approach to Scripture. In fact, that’s what I would expect him to do. What I wouldn’t expect, however, is for him to fail even to engage my approach, but rather to distort it into a different approach altogether, so that he can portray me as a more radical critic than I actually am, to the good pleasure of his constituents.

Burk continues: “Stark anticipates an objection: If the texts deserve censure, then why pay attention to them at all, much less give them some kind of authoritative, canonical status? He answers:

To do so is to hide from ourselves a potent reminder of the worst part of ourselves. Scripture is a mirror. It mirrors humanity, because it is as much the product of human beings as it is the product of the divine…. It mirrors our best and worst possible selves. It shows us who we can be, both good and evil, and everything in between. To cut the condemned texts out of the canon would be to shatter that mirror. It would be to hide from ourselves our very own capacity to become what we most loathe. It would be to lie to ourselves about what we are capable of. It would be to doom ourselves to repeat history (218-19).

“So Stark says that the church must appropriate Scripture’s regulative authority in two ways: one, it must face head-on the Bible’s moral and theological deficiencies, and two, reject for its own life the negative examples in the Bible. In other words, the church should learn to shun the evil ways of the God of Scripture.”

Another flagrant deception. Burk knows full well that I argue that there are multiple depictions of God in the collected works that we call Scripture. I do not believe in a “God of Scripture.” I contend that there are “Gods” in the collected works that comprise the Bible, and some of them are good depictions of God, while others are morally or theologically deficient, for reasons I have provided in detail, none of which Burk has engaged in his “critical review.” So again, the reader of Burk’s review will come away with the false impression that I reject both “the Bible” and “the God of Scripture,” when in fact that is not what I do at all. Burk cannot but impose his own fundamentalist view of the Bible onto me in his attempts to discredit me. Once again, the problem is not with me, or with the Bible, but with the fundamentalist approach to the Bible. Burk’s fundamentalist mind seems to be incapable of even entertaining a perspective other than his own. He is forced to cast me as his opposite within the same fundamentalist paradigm, rather than rightly identifying me as someone with a different paradigm altogether.

Burk continues: “Stark gives several illustrations of how his hermeneutic works out in practice. Since Scripture reveals that both polytheism and monotheism underwrite ideologies of slavery, war, genocide, and racism, the church must reject both polytheism and monotheism. Instead, Christians should embrace a new ‘conception of the divine nature’—one that recognizes its non-trinitarian ‘plurality’ (221).”

Yet more flagrant distortion, made possible by the insertion of words into my mouth that I never uttered. First, I never stated that what we needed was a “new” conception of the divine nature. “New” is Burk’s word. And neither am I rejecting monotheism, although I’ll allow for some honest misunderstanding here. I am not rejecting monotheism, but critiquing aspects of its origins on the theological scene. Perhaps Burk just can’t fathom that I can be critical of how a perspective came into existence historically (for dubious political reasons) without rejecting that perspective wholesale.

But here’s the real distortion. Burk claims that my “new” conception of the divine nature is one that recognizes its “non-trinitarian” plurality. “Non-trinitarian?” Again, Burk has put words in my mouth that totally distort my actual position. What he describes as my “non-trinitarian” conception of a divine nature in plurality is actually my description of Trinity! My words:

The inadequacies of the text reveal the need for a conception of divine nature that is difference in harmony, unity in diversity. The divine is not one, but neither—in its plurality—is the divine at odds with itself. Thus, while polytheistic and monotheistic conceptions of God have been exposed as mirror reflections of our worst selves, a conception of the divine as difference in harmony represents an ontology—a divine reality—that calls upon humanity to better itself and to become the mirror image of the sacred reality.

I’ll grant again that my words are open to some misunderstanding, but part of that is intentional in order to challenge the reader to stretch a “well-worn” paradigm. But never did I use the term “non-trinitarian,” and while I did say that the divine is “not one,” I also described it as “unity in diversity.” Last time I checked, “unity” means “oneness.” So Burk’s misunderstanding just comes from a refusal to accept the challenge my language presented. When I said that the divine is not “one,” I was referring back to my earlier critique of monotheism as an originally imperialistic ontology. If my language is confusing to Burk, my response is that all Trinitarian language is similarly confusing. That’s because we’re talking about God. So deal with it.

Burk continues: “Since Scripture affirms the nobility of human sacrifice, Christians should recognize their own evil propensity for human sacrifice. Once again in Stark’s own words,

Yet we continue to offer our own children on the altar of homeland security, sending them off to die in ambiguous wars, based on the irrational belief that by being violent we can protect ourselves from violence. We refer to our children’s deaths as “sacrifices” which are necessary for the preservation of democracy and free trade. The market is our temple and must be protected at all costs. Thus, like King Mesha, we make “sacrifices” in order to ensure the victory of capitalism over socialism, the victory of consumerism over terrorism (222).”

A couple of things should be noted here. First, again, Burk has stated that my position is that “Scripture” affirms the nobility of human sacrifice. But of course, my actual position is that some earlier texts within Scripture affirm the nobility of human sacrifice (to Yahweh only), while others from later periods reject the institution of human sacrifice as immoral. Once again, Burk has hidden from view a major and crucially significant aspect of my argument.

The other thing I’ll point out is how transparent Burk’s motivation for quoting this particular excerpt from my book is. He is writing to a conservative Evangelical audience, for whom U.S. wars and so-called “free trade” are as sacred as the doctrine of inerrancy itself. So Burk doesn’t have to comment on this quote; he just has to quote it, and I’m further discredited in the eyes of many if not most of his constituents. The irony of course is that I’m the one here actually critiquing worldly values that contradict both Hebrew Bible (economic) and New Testament (economic and peacemaking) values.

Burk continues with a left-handed compliment: “This is a learned book that is well acquainted with critical biblical scholarship.” My book is, for Burk, acquainted with “critical” scholarship, but not well enough acquainted with fundamentalist scholarship. As if I didn’t undergo four years of training in fundamentalist scholarship at my conservative Bible College. Burk continues:

“Nevertheless, for a number of reasons, The Human Faces of God does not deliver on what it promises. Stark attempts to offer both a convincing case against inerrancy and a viable, alternative way of reading the Bible as Christian Scripture. He fails at both aims.”

It will be interesting to see how Burk supports his claim that I failed at both aims, especially how he supports his claim that I failed the second. But first the first:

“None of the arguments that [Stark] offers against inerrancy are new (as he himself acknowledges on page xvii), yet he treats his interpretation of the material as if it were the settled scholarly consensus.”

Actually, while I did say something like this, the fact remains that I have carried some of the debates forward in new ways, for instance in my discussion of the David and Goliath legend, and in my extensive critiques of the genocide apologists, as well as in my extensive critique of Tom Wright’s reading of the Olivet Discourse. But whatever. Nothing new. That’s apparently a criticism. (See why that’s ridiculous above.)

Burk continues: “He promises to pay inerrantists the ‘deep respect of extensively engaging their arguments’ (xvii) and then neglects to interact with leading scholars who have defended inerrancy over the last thirty to forty years.”

Now this, I am forced to say, reflects Burk’s agenda very clearly, and an actual problem with my statement about engaging inerrantists not at all. The reason this reflects Burk’s agenda is because this is an initial criticism he made of my book several months ago, before he had finished reading it, to which I responded on his blog. In that early blog post, Burk quoted me saying that I wished to pay inerrantists the deep respect of extensively engaging their arguments, and wrote in response: “I have to say that I am forearmed against believing that Stark will meet the ideal of that last sentence. I have just perused Stark’s bibliography, and there is not a single reference to the work of Greg Beale, Timothy Ward, D. A. Carson, or John Woodbridge. Has he really paid his respects? It doesn’t sound like it. So far, not so good.”

But in the comment thread I responded directly to this criticism, which is based upon a misunderstanding of my statement. I wrote: “I had in mind my extensive engagement with different Evangelical apologists, Denny, such as Christopher Wright, Tom Wright, Gleason Archer, Walter Kaiser, Norman Geisler and the other drafters of the CSBI, etc. But many of the arguments made by your favored apologists are not original to them, and are of course addressed in my book as well. I look forward to reading your book review.” In a later comment, I stated again, “I’m sure Denny will have much to say by way of criticism, but it’s probably not the best idea to critique it for being something other than what Denny ostensibly expected it to be.”

I then wrote: “The main object of my criticism when it comes to inerrancy is the CSBI, and that’s because of the controversial role it has played in recent years within the ETS. I engage the CSBI extensively, and that took up enough space. Moreover, my arguments there cover the kind of argument Beale makes when he tries to prove inerrancy by arguing that certain texts claim something like inerrancy. At any rate, the quote Denny pulled from my preface says that I engaged ‘extensively’ with Evangelicals, not ‘exhaustively.’ Denny’s rhetoric depends upon a conflation of those two domains. I’m sorry if I disappointed him, but again, I think this has more to do with Denny’s own expectations than anything I actually claimed about the content of the book. Nevertheless, I still look forward to his review. I expect that after he’s finished reading it, he’ll have a better grasp of the approach I’m taking and the primary arguments I’m making. It’s difficult to have a whole perspective based on having read the preface and bibliography.”

Apparently I was wrong. Or rather, even after acknowledging my response to this misguided criticism, Burk was not diverted from his agenda of portraying me as dishonest by claiming to engage inerrantists extensively, which I in fact did. Burk is certainly within his rights to critique me for not engaging his pet inerrantist scholars, but he’s being deceptive by trying to pit my selected bibliography against the statement in my preface, once he had been informed that he was misreading my intent. Once again, “authors intended meaning” doesn’t always play a role in fundamentalist hermeneutics. But let’s move on and address Burk’s specific concerns about whom I failed to engage in my book.

Burk writes: “For example, Stark lodges extensive complaints against New Testament authors’ use of the Old Testament (19-20, 29), yet he has not one word of interaction with the work of Greg Beale or other inerrantists who have done extensive work in typology.”

Burk seems to think my discussion of pesher is some sort of attack on the Bible. Rather, what I’m doing is describing the hermeneutic operative in the late second temple period. My aim here isn’t to discredit the Bible but simply to describe the hermeneutic that was operative among many apocalyptic sects, such as the Qumran sect, and the Jesus movement. The actual response of many of my readers, even those who aren’t Christians, was very positive in the sense that they were able to see that, for instance, when Matthew alluded to Isaiah 7 in his virgin birth narrative, Matthew wasn’t “abusing” the text; he was simply doing what biblical interpreters did in his day. This is only a problem for the specific brand of inerrantists who insist upon a strict historical-grammatical interpretation of Scripture. But my point was that that is a foreign imposition onto the text that isn’t at home in the world of the late second temple writers. So many of my readers were able to look at Matthew with new eyes; even some who formerly thought Matthew was just a bad or dishonest interpreter came to appreciate him for what he really was: a first century Jewish author operating as first century Jewish authors operated, and with a good deal of artistry. The reason I didn’t engage with fundamentalist perspectives on “typology” is because that would have been peripheral to the point of this section in my book, which in my mind was a point that very much respected the biblical text. I could engage Beale in another context, and point out all the reasons why much of his language hasn’t been adopted by the consensus, or I could write the book I set out to write. So Burk’s criticism just misses the point.

He continues: “Stark dismisses out of hand the notion that inerrancy is the established position of the church (17, 32), yet he has not one scintilla of interaction with John Woodbridge’s work (nor does he cite the Rogers and McKim proposal).”

Now this is ridiculous. I do not “dismiss out of hand” the notion that inerrancy is the established position of the church. I provide numerous reasons why it’s not as simple as all that. I’ve read Woodbridge’s book and the Rogers and McKim book twice each, but I didn’t cite them because I think both approaches are very much wrongheaded. The debate they have between them goes in all sorts of directions it doesn’t really need to go, so to engage them would have been, from my perspective, a huge diversion. The incontrovertible fact is that, for much of church history, while certain important figures made statements about the infallibility or inerrancy of the Bible, they did not share the Chicago inerrantists’ commitment to a historical grammatical hermeneutic, and that makes all the difference. This is a fact which Woodbridge bungles in his work. And this is a point I made very clearly and with extensive primary-source support in my book.

Recall our discussion just above of Gregory of Nyssa, a hugely important figure for early orthodox Christianity. The Bible could be inerrant for him, but emphatically and clearly not in the same way it was for the Chicago inerrantists, because for Gregory, the historical-grammatical reading of certain texts could produce an image of God that is morally reprehensible and must be rejected. Thus, he opted for allegory, which the Chicago inerrantists (due to their apparently unconscious commitment to a modernist epistemology) emphatically reject. So here’s one big case where church history is at odds with the claims made by these modern-day inerrantists. And I detailed others as well in my book.

Origen does precisely the same thing as Gregory: he is confronted with a text that on a historical-grammatical reading is offensive, a text that portrays God in ways that are not worthy of God. (For Origen, it was the Canaanite conquest texts.) He confronts these texts as immoral, and denies that a literal interpretation is possible, if the Bible’s authority is to be preserved. So, like Gregory, Origen opted for an allegorical interpretation, which the Chicago inerrantists reject. And as I pointed out in my book, even Augustine, who had a change of mind on allegory, and later adopted a “literal” hermeneutic, still did not have a commitment to a historical-grammatical hermeneutic. For Augustine, as I showed, the “literal” meaning of the text was not the same thing (necessarily) as the historical-grammatical meaning. In fact, even up until Luther, the “literal” meaning was understood as the theological meaning, which sometimes corresponded to the historical-grammatical meaning, but certainly not always. This is incontrovertible, and is the established consensus position of actual patristic scholars the world over.

I studied these issues under Prof. Paul Blowers (PhD. Notre Dame), who served as vice-president and then as president of the North American Patristics Society. Dr. Blowers himself has written quite extensively on patristic hermeneutics, and I had discussions with him about just this issue as I was writing my book. The fact is (as I showed amply well), while the fathers did make statements about the authority of scripture, the infallibility of scripture, and in a few cases about the inerrancy of scripture, their hermeneutic was so radically different from the Chicago inerrantists that what we actually have are two very different doctrines of inerrancy, one in which the Bible is authoritative or inerrant, but its “inerrant” meaning may not be the historical-grammatical meaning, and one in which the Bible must be deemed inerrant in a strictly historical-grammatical sense.

Of course, Burk discloses none of my extensive discussion of these issues to his readers. Rather, he lies by stating that I simply “dismiss out of hand” the view that I spend several pages undermining. So I do apologize if Burk was offended by the fact that I didn’t refer to Woodbridge, even though my arguments had people like Woodbridge in mind. But what we see here is not a deficiency in my argument, as much as a tactic employed by Burk to make me look uninformed, a tactic which also has the virtue of hiding all the actual information I provided from his readers.

Burk continues: “I daresay that there is not a single objection to inerrancy that he raises that has not already been ably answered in the relevant literature. Yet Stark goes right on as if his case is the only one to be made.”

This is of course hogwash. How can I be “going right on as if my case is the only one to be made” when I’m arguing against other cases the whole time? Pure rhetorical maneuvering here. And as for this claim that there is “not a single objection to inerrancy . . . that has not already been ably answered in the relevant literature,” all I can say is, citations please! Where is the inerrantist, for instance, who “ably answers” my point in the David and Goliath text that while all of the Philistine giants had Philistine names of Indo-European (and not Semitic) origin, we’re supposed to believe that Goliath’s parents named his brother “Lachmi,” a Hebrew word meaning “my bread,” which is actually taken from the word “Bethlechem” as it appears in the original version of the story? Who has “ably answered” this objection? I could go on with a list a mile long of objections I made that I know have not been “ably answered.” But of course, as I showed in my book, for an inerrantist, any “possible” answer that preserves inerrancy is to be preferred to any “plausible” answer that disproves inerrancy. Yes, yes, inerrantists are forever writing “answers” to the challenges posed to their worldview by consensus scholarship. Why then does the scholarly consensus not affirm inerrancy? It must be a massive liberal conspiracy.

Burk now attempts to provide an actual example of a case where I “trot out old objections that have already been answered.” Of course, for his sole example he selects a text that is entirely peripheral to my main arguments, and he also completely misunderstand the nature of my argument in this section, but we’ll get to that. Burk writes:

I could multiply examples in which Stark trots out old objections that have already been answered, but I will limit myself to just one. In an attempt to show that inerrantists do not really accept the Bible’s literal sense, he appeals to 1 Timothy 2:12-14 and the fact that many inerrantists allegedly reject Paul’s teaching that women are “inherently more susceptible to deception” (16- 17). Stark says that “the most common strategy to explain away this blatant misogyny” is to impose a distinction between the cultural and the universal (41). For Stark, this is prima facie evidence that inerrantists cannot accept what the Bible really teaches and that they do not practice the hermeneutic that the Chicago Statement preaches. Yet anyone familiar with the literature knows that this is not the “most common strategy” used by inerrantists in dealing with this text. Stark appears oblivious to the work of Doug Moo, Tom Schreiner, and many others who argue on exegetical grounds that the prohibition on female teachers has to do with the order of creation, not with the relative gullibility of women.

All right. Let’s break this down. First, another distortion. Burk writes, “In an attempt to show that inerrantists do not really accept the Bible’s literal sense, he appeals to 1 Timothy 2:12-14 and the fact that many inerrantists allegedly reject Paul’s teaching that women are ‘inherently more susceptible to deception’ (16- 17).” By quoting my words, “inherently more susceptible to deception,” Burk has made it seem as though I have argued that inerrantists reject “Paul’s teaching” (in Burk’s words). But no. Obviously the majority of inerrantists don’t believe that this is what the author of Timothy is saying. So, contrary to Burk’s characterization, I am not saying that inerrantists are “rejecting Paul’s teaching.” Rather, they argue that Paul is teaching something else. That’s my whole point. That the author of Timothy taught that women are “inherently more susceptible to deception” is my position, not that of most inerrantists, although I do know quite a number of inerrantists who interpret this passage correctly and agree with it!

Next point: “Stark says that “the most common strategy to explain away this blatant misogyny” is to impose a distinction between the cultural and the universal (41). For Stark, this is prima facie evidence that inerrantists cannot accept what the Bible really teaches and that they do not practice the hermeneutic that the Chicago Statement preaches. Yet anyone familiar with the literature knows that this is not the “most common strategy” used by inerrantists in dealing with this text.”

This is incredible. Burk has tried to correct my statement that the “most common” strategy among inerrantists is to take the cultural vs. universal route. He objects by pointing out a handful of scholars who don’t take this approach. Give me a break. I’m not denying that there are other strategies; that’s in fact implicit in what I said. But go into any mainstream Evangelical church in North America and take a poll: the majority will say that this passage applied to that cultural context, but not to our context today. There are countless evangelical scholars who have argued this over the past several decades. Burk is really stretching to portray me as uninformed. But, Burk has put his foot in his mouth, because Douglas Moo himself (whom Burk cites against me) referred to the cultural vs. universal interpretation as “by far the most popular approach among those who do not think that 1 Timothy 2:12 has general application.”1

Of course, I’m familiar also with Moo et al. who try to do away with the second clause of the author’s justification for his rule that women should be silent in the church. But of course, their arguments fail, and certainly haven’t persuaded the consensus of critical scholars (and “critical” applies to a number of relatively conservative believers as well). Here’s Moo’s argument. I’ll break it up and respond piecemeal:

If the issue, then, is deception, it may be that Paul wants to imply that all women are, like Eve, more susceptible to being deceived than are men, and that this is why they should not be teaching men! While this interpretation is not impossible, we think it unlikely. For one thing, there is nothing in the Genesis accounts or in Scripture elsewhere to suggest that Eve’s deception is representative of women in general.

This objection is only relevant to inerrantists who require that all scripture must agree with itself. Moreover, it ignores the time period and the contemporaneous Jewish literature. In fact, although not for Moo, Ben Sira was a part of the Bible of the earliest Christians. And in Ben Sira we find statements such as this one: “From a woman sin had its beginning, and because of her we all die” (Sir 25:24). Misogyny was pervasive throughout the Greco-Roman world and in its literature, and it was rampant in second temple Jewish literature as well, in which Eve frequently played the role of the evil woman responsible for all the world’s ills. Eve was representative of the folly of all women as well. This is the case in Ben Sira. Let’s look at the preceding verses of the same passage:

Any iniquity is small compared to a woman’s iniquity; may a sinner’s lot befall her! A sandy ascent for the feet of the aged— such is a garrulous wife to a quiet husband. Do not be ensnared by a woman’s beauty, and do not desire a woman for her possessions. There is wrath and impudence and great disgrace when a wife supports her husband. Dejected mind, gloomy face, and wounded heart come from an evil wife. Drooping hands and weak knees come from the wife who does not make her husband happy. From a woman sin had its beginning, and because of her we all die. (Sir 25:19-24)

As is clear, the author attributes the folly of all women to its source in the first woman, Eve. So Moo’s first objection really has no import except to those predisposed to exclude Ben Sira from consideration, even though it was in the canon of the Christians at the time 1 Timothy was written.

And let’s not forget how prominent early Church Father Tertullian understood this passage from 1 Timothy:

God’s judgment on this sex lives on in our age; the guilt necessarily lives on as well. You are the Devil’s gateway; you are the unsealer of that tree; you are the first foresaker of the divine law; you are the one who persuaded him whom the Devil was not brave enough to approach; you so lightly crushed the image of God, the man Adam; because of your punishment, that is, death, even the Son of God had to die. And you think to adorn yourself beyond your “tunics of skins”? (CSEL 70.59)

Moo continues:

“But second, and more important, this interpretation does not mesh with the context. Paul, as we have seen, is concerned to prohibit women from teaching men; the focus is on the role relationship of men and women. But a statement about the nature of women per se would move the discussion away from this central issue, and it would have a serious and strange implication. After all, does Paul care only that the women not teach men false doctrines? Does he not care that they not teach them to other women?”

This objection is just a grasping at straws. Citing the woman’s deception in the Garden as a justification for the prohibition of women teaching men is not a “move away” from the point; it’s an argument in support of the point. The argument is that, since man came before woman, a woman ought not to have authority over a man, and since woman was deceived (and not man!), a woman ought not to teach in the church. Note that 1 Timothy 14 actually does say, “Adam was not deceived, but the woman was deceived,” which is of course patently false. Adam was deceived, by Eve, who was deceived by the serpent. But moving on from that point, Moo’s objection that this reading doesn’t make sense because, “does Paul care only that women not teach men false doctrines? Does he not care that they not teach them to other women?” is a total red herring, for two reasons: (1) The context is teaching in the church, not just teaching in general. So in the church, if a woman were teaching, she would have been teaching over men and women simultaneously. So Moo’s rhetorical question just misses the point. (2) Paul doesn’t have to be concerned about women teaching other women in the privacy of homes if in fact women are to be in submission to their male masters, which is also Paul’s point, because “Adam was formed first, then Eve.” So Moo’s objections just fail utterly to dispense with this deeply misogynistic perspective enshrined in our canon. The plain fact is, as the consensus holds, the author of 1 Timothy argued that women should not teach in church because they are inherently more susceptible to deception than men, as evinced by Eve, before the fall.

Moo continues:

More likely, then, verse 14, in conjunction with verse 13, is intended to remind the women at Ephesus that Eve was deceived by the serpent in the Garden (Genesis 3:13) precisely in taking the initiative over the man whom God had given to be with her and to care for her. In the same way, if the women at the church at Ephesus proclaim their independence from the men of the church, refusing to learn “in quietness and full submission” (verse 11), seeking roles that have been given to men in the church (verse 12), they will make the same mistake Eve made and bring similar disaster on themselves and the church. This explanation of the function of verse 14 in the paragraph fits what we know to be the general insubordination of some of the women at Ephesus and explains Paul’s emphasis in the verse better than any other alternative.2

But against Moo, we’ll quote Moo:

However, Paul tells us remarkably little about the specifics of this false teaching, presumably because he knows that Timothy is well acquainted with the problem. This means that we cannot be at all sure about the precise nature of this false teaching and, particularly, about its impact on the women in the church—witness the many, often contradictory, scholarly reconstructions of this false teaching. But this means that we must be very careful about allowing any specific reconstruction—tentative and uncertain as it must be-to play too large a role in our exegesis.3

So according to Moo, this must not play too large a role in his exegesis, but after all else fails, he’ll use it to salvage a problematic text. And Moo, who argues that 1 Tim 2:12-14 is not limited to a specific context, but is of universal import, finally winds up arguing that one part of verse 14 was limited to a specific context, even though he argues that Eve’s deception is pre-fall and therefore technically a part of the order of creation argument.4 He also cites 2 Tim 3:6-7 as evidence that women were being deceived by false teachers at Ephesus. Let’s look, indeed, at how women are described by the author there:

For among them are those who make their way into households and captivate silly women, overwhelmed by their sins and swayed by all kinds of desires, who are always being instructed and can never arrive at a knowledge of the truth.

What a fair-minded description of women! “Silly.” “Swayed by all kinds of desires.” “Always being instructed, never making up their minds.” “Overwhelmed by their sins.” Sounds remarkably like another women we’ve met in the previous letter, who was used to provide a universal justification for the subordination of women to men: “For Adam was formed first, then Eve; and Adam was not deceived, but the woman was deceived and became a transgressor. Yet she will be saved through childbearing, provided they continue in faith and love and holiness, with modesty.”

Moo hasn’t “ably answered” any objection here. He’s simply providing a way out for inerrantists who don’t really like what this biblical text says about women.

And as for Burk’s claim that I’m apparently “oblivious” to the arguments of Moo et al., that’s of course just nonsense, as I myself entertained Moo’s views back in my fundy days. Burk’s whole criticism here, of course, founders on a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of my argument in this section of the book. I’m not arguing that every inerrantist adopts the example inerrantist position I’m providing. But I was offering a long series of different texts and pointing out that every inerrantist will have trouble with at least one of them! Every inerrantist is inconsistent somewhere. If not with 1 Timothy 2, then with one of the other texts I cited, surely. That was point: not that inerrantists don’t exist because they don’t agree with any of these biblical passages, but that inerrantists don’t exist because all it takes is for them to disagree with one! That’s the point I made very explicitly in the book; it’s very clear. And so Burk’s criticism here just displays either that he wasn’t reading me very closely, or that once again he is intentionally distorting my argument in order to make it appear that I’m a little nutty. Once again, I can’t decide which option would be giving him the benefit of the doubt, because neither is very desirable, I wouldn’t think.

Burk now moves to his criticism of my alternative proposal for how to retain these problematic texts in the Bible as scripture:

Not only does Stark fail to produce a convincing argument against inerrancy, he also fails to offer a viable alternative. His proposal to read the Bible as a “condemned” text is clever but transparently bogus. It is a little bit like asking an abused wife to admire her abusive husband because of the “mirror” he provides into her own corruption. It is patently absurd, and I doubt that very many actual churchgoers will be compelled to respect the Bible as “scripture” based on the mountain of deficiencies that Stark alleges. If anything, Stark has given readers more reasons to give up on the Bible altogether.

What Burk does here is to replace my metaphor for the condemned texts with his own metaphor, and then to ridicule his own metaphor as absurd. My metaphor of course was to treat the problematic texts as we do the alcoholic uncle in the family:

Certain texts in our scriptures are like that alcoholic uncle we all know. It is easy enough to avoid the problem. Like the uncle, many of the texts don’t show up on our doorstep very often. But when they do show up (and they inevitably do) they are only going to do damage to the family unless the family is willing to sit down and hold an intervention, to confront the problem directly, and to set the ground rules for interaction within the community. Once these ground rules have been set in place, fruitful interaction between the troublesome text and the faith community becomes possible. The “alcoholic uncle” can continue to be a part of the family, and he can actually learn to participate in unique and fruitful ways, providing he is able to acknowledge that he has, and always will have, the disease. In order to save such texts, they must be confronted, their troublesome nature must be truthfully characterized, and they must be branded for life. Only then will they be able to serve a useful function within the life of the community. . . . The reality is that they are a part of our tradition whether we like it or not. Thus to extricate them from the canon would be a massive dishonesty. In condemning them, we must own them. As participants in the Judeo-Christian tradition, we are responsible for these texts, just as the good family takes responsibility for the alcoholic uncle. In order to mitigate the damage these texts can do—the extent of which history has borne out—we must keep these texts close to us. Casual dismissals of the Crusades and of missionary colonialism as aberrations of the faith fail to take responsibility for the complicity of our scriptures in such moral atrocities. The true modern-day Marcions are those who refuse to take responsibility for the Bible’s role in the violent expansion of Western civilization.

My metaphor is perfectly apt. It’s Burk’s own metaphor that doesn’t fit; and that’s why it doesn’t appear in my book. He clearly just can’t understand the words I wrote (what does that say about his ability to interpret texts he doesn’t like in general?). I’m not suggesting that we should “admire” these morally problematic texts, like “asking an abused wife to admire her abusive husband.” I’m saying we must confront these texts for what they are, but that we must also take responsibility for them, because they’re part of us whether we like it or not. That doesn’t mean we allow them to abuse us, as per Burk’s ridiculous metaphor. On the contrary, I’m saying that they have been abusing us. They’ve been abusing our intellect, our moral integrity, abusing our politics and abusing the Other through us. What I’m calling for is for us to stop letting these texts abuse us, to confront them, but also to allow them to remain as reminders to us that we are always capable of being the abusers. How hard is that to understand? Apparently for Burk, it’s very difficult. In reality, the real abusive husbands in this scenario are the inerrantist pastors and apologists who tell those who are struggling with these morally monstrous texts to suck it up and deal with it. I’ve seen this kind of spiritual abuse over and over and over again, and I’ve seen its devastating effects on Christians all too often. And God damn it, I’ve had enough. Haven’t you?

Burk continues with a final bout of nonsense: “In the end—even though he does not say so in so many words—Stark himself has given up on the Bible.” Actually, if he had been paying attention, exactly the opposite is the case. My position is marked rather by a stanch refusal to give up on the Bible. What I have actually given up on is the debilitating and demoralizing fundamentalist approach to the Bible.

Burk continues: “He confesses that he rejects monotheism and the substitutionary atonement of Christ and that he is not in any sense an orthodox Christian (242).”

No, I have not rejected monotheism. It’s just that Burk has rejected basic reading comprehension. I did not state that I have rejected the substitutionary atonement of Christ; I simply was critical of a bastard but popular version of the biblical doctrine. I understand the doctrine rooted in its Jewishness, not in a medieval Anselmian sense, and I quite like it actually, when properly understood. And I did not say that I was “not in any sense an orthodox Christian.” I said that I am not an orthodox Christian, because no such thing exists—a point obviously lost on Burk.

Burk continues: “We have to conclude that Stark’s approach is less a reading of Scripture than it is a raging against it.”

I agree that Burk has to conclude this. But he doesn’t have to conclude this because it’s true; he has to conclude this because he read a very different book from the one I wrote. It’s his own fundamentalist paradigm that forces him to see things this way. But of course, take a look at the blurbs by all the Christians in the first pages of my book, and on the back, and it’s clear that the Christians there don’t share Burk’s opinion about the nature of my reading of Scripture. I do not “rage against” the Bible. I love the Bible; and because I love it, I am compelled to confront the problematic texts within it, while also being compelled to keep those selfsame problematic texts very close to me, for my own benefit.

Burk continues: “Stark loathes the God of the Bible and filters out any depiction of God in Scripture that does not fit into the Stark moral universe. Stark stands over Scripture as its judge. Indeed, his hermeneutic requires it. And he wants readers to join him in his cynical scrutiny of the Bible. The shortcomings of The Human Faces of God, however, are extensive and serious, and there are more than enough reasons for readers not to follow Stark down the dead-end trail that he is walking.”

More cynical waste and distortion. Burk should really be ashamed of himself for writing such a terrible book review. I don’t loathe the God of the Bible. Once again, there are many depictions of God in the Bible, and many of them I absolutely love, many I approve of while they make me yet very uncomfortable, and many of them I condemn, out of zeal for God and justice, which must be the same thing, if God is to be worthy of any praise. And yes, with Gregory, and Origen, and C. S. Lewis, and so many other Christians, there are times when we must stand in judgment over certain parts of the Bible. As Lewis said:

Yes. On my view one must apply something of the same sort of explanation to, say, the atrocities (and treacheries) of Joshua. I see the grave danger we run by doing so; but the dangers of believing in a God whom we cannot but regard as evil, and then, in mere terrified flattery calling Him ‘good’ and worshiping Him, is still greater danger. The ultimate question is whether the doctrine of the goodness of God or that of the inerrancy of Scriptures is to prevail when they conflict. I think the doctrine of the goodness of God is the more certain of the two. Indeed, only that doctrine renders this worship of Him obligatory or even permissible.

To this some will reply ‘ah, but we are fallen and don’t recognize good when we see it.’ But God Himself does not say that we are as fallen as all that. He constantly, in Scripture, appeals to our conscience: ‘Why do ye not of yourselves judge what is right?’ — ‘What fault hath my people found in me?’ And so on. Socrates’ answer to Euthyphro is used in Christian form by Hooker. Things are not good because God commands them; God commands certain things because he sees them to be good. (In other words, the Divine Will is the obedient servant to the Divine Reason.) The opposite view (Ockham’s, Paley’s) leads to an absurdity. If ‘good’ means ‘what God wills’ then to say ‘God is good’ can mean only ‘God wills what he wills.’ Which is equally true of you or me or Judas or Satan.

I happen to stand in a long and serious tradition of Christians who take the Bible seriously by refusing to allow its worst texts to deform our moral integrity as agents of God. Burk thinks that I have “failed” to provide an alternative to his fundamentalism, but all that means is that I have failed to provide a fundamentalist alternative to fundamentalism. He thinks that not many Christians will or ought to follow me on this road. I’m of course following my forebears, going back to the great debaters in the Bible itself: Job, Qohelet, Amos, the author of Jonah, Jesus of Nazareth, and so on. And Burk may not realize it because he lives in a fundamentalist bubble, but when it comes to Christians, my ilk have his ilk outnumbered. Neither of course is he aware of the literally hundreds of emails and messages I’ve received from Christians who have affirmed their solidarity with me or thanked me for helping them salvage a faith crumbling under the oppressive weight of fundamentalist Evangelicalism. And while my faith was never so much in jeopardy as the many I’ve encountered wandering near this road, I too owe a debt to my forebears who have preceded me on it, who have lit this terrifying and oft times ambiguous path with lamps of unflinching candor. If it were a choice between the God of Denny Burk and no God at all, then it would be out of zeal for God that I would proclaim myself an atheist. Fortunately, as the majority of us realize, this sacred world ain’t so goddamned black and white.