Posted: November 22, 2011 at 8:05 pm

My thanks to Steven Garmon for taking the time to write a critical review of HFG. My thanks also for the respectful tone Steven maintained despite his numerous disagreements with my arguments.

Unfortunately, Steven’s criticisms do not hold up against much scrutiny. First, Steven writes:

It seems to me that Stark is quick to point fingers at fundamentalists for trying to force God and the Bible into their own little pre-conceived box, however after reading this book it is apparent to me that Stark is guilty of the same.

This is a claim that Steven fails to substantiate in his review, and one he’d have a hard time substantiating given my apophatic theological approach.

Steven critiques chapter four:

In Chapter 4 Stark begins to pick away at inerrancy by claiming that the first authors of the Bible were actually polytheists. My reaction after reading this chapter was “so what?” I hold an incarnational view of scripture, so I believe that God accommodated Himself to the authors of the Bible.

This is a “solution” to the problem that comes under direct critique in my book, but Steven does not address my criticisms. Unfortunately, an accomodationist view does nothing to change the fact that early texts assume and declare the existence of other deities, while later texts flatly deny them. Now, a Christian may hold to a view of scripture that allows for “progressive revelation,” but this is an approach expressly rejected by the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy which is the brand of inerrancy under scrutiny in my book. Steven continues:

Obviously, Israel was surrounded by cultures where polytheism, and pantheism I might add, were prevalent.

Pantheism? I’d like to see the documentary evidence for the prevalence of pantheism in the ancient Near East.

Therefore, it makes perfect sense that the authors, at least at the beginning, still believed in multiple Gods. All this portrays is that God meets his beloved chosen people where they are. It doesn’t show that the Bible cant be trusted.

Unfortunately, this claim does not hold water when Yahweh himself is portrayed frequently in scripture as one who believes in the existence of other deities.

In Chapter 5 Stark attempts to show that God was pleased with child sacrifice and even commanded it. This chapter seemed the weakest to me and it is filled with series of mental gymnastics to make his point.

Another claim Steven fails to substantiate. That early Israelite texts sanctioned child sacrifice in the name of Yahweh is a view held by the majority of Hebrew Bible scholars. I provide an introduction to the evidence underwriting this consensus position. As far as mental gymnastics, Steven offers one example which only serves to display Steven’s unfamiliarity with the relevant scholarship and his complete misapprehension of my position. He writes that I mention

in passing Jeremiah 19:5-6 which clearly states that God is completely against child sacrifice but he quickly dismisses it. This is a common aspect of Stark’s thought that is carried out often (as we’ll see later) where he sometimes cherry-picks things from scripture that he believes can make his point and disregards things that can hinder it.

This is an unfortunate misrepresentation of the facts. In reality, I do not “dismiss” Jeremiah 19:5-6 because it is inconvenient for my thesis. My thesis (the consensus thesis) includes the fact that Jeremiah was a late voice who rejected the institution of human sacrifice, an institution which was previously official. That Jeremiah rejects human sacrifice is not evidence against my position. It only serves to confirm the reconstruction I provide which states that human sacrifice was prevalent in earlier Israelite and Judean religion only to come under scrutiny later, by Jeremiah, Ezekiel and others in a later period. That Steven thinks Jeremiah 19:5-6 is evidence against my position only shows that he did not read my argument with any degree of care. He continues:

He mentions the incident with Jephthah’s daughter, but he makes it seem as if scholars are clear about the outcome, of which they are not. But even if he is correct in his claim, there is nothing in the text that says God approved of it.

Both of these claims are false. First, while a few conservative scholars have argued that Jephthah did not in fact go on to sacrifice his daughter, this is a fringe position that enjoys no support within mainstream scholarship. The vast majority of scholars are very clear about the outcome. Second, there is more than one indication in the text that God approved of the sacrifice, as I discuss both in my book and more extensively in my critical review of Paul Copan’s book, Is God a Moral Monster? Steven continues:

Chapter 6 deals with the “genocides” committed in the name of God. Now, first off I want to say that Stark already tips the scales in his favor by using the term genocide. This basically hinders the reader from remaining neutral to Stark’s arguments when he starts with the term genocide.

Perhaps if Steven will take the time to look up any definition of genocide, he’ll see that whether we approve or disapprove of the actions of the Israelites in the conquest of Canaan, the conquest is clearly and accurately described as a genocide. I discuss this in detail in my review of Copan’s book.

However, I see no problem whatsoever with God carrying out judgement on nations. He is the creator and giver of life and He has the right to take it away. Stark says that if God knew that the Canaanites were going to become so depraved then why didn’t He do anything to stop their behavior. My response was “Who says He didn’t?”

The answer is, the Bible says he didn’t, and quite frequently.

But even if God didn’t intervene with the Canaanites, so what? We are all responsible for our actions and its not unfair for God to enact his judgement when He feels fit.

Unfortunately, Steven has opted not to engage the pages and pages of argumentation I provide in HFG showing why this attitude creates more problems than it solves. Simply ignoring my arguments does not constitute a counter-argument. Steven continues:

In Chapter 8 Stark progresses [sic] the argument that Jesus wrongly predicted His second coming. This is where we see Stark act out a textbook definition of a double standard. Up until this point in his book he has made the claim that the Bible cannot be trusted to accurately portray God. But, when He finds a verse that is uttered by Jesus himself that he thinks cushions his argument, he doesn’t strain at all to credit its accuracy.

Rather than a “textbook definition of a double standard,” this is rather a textbook example of a careless reader. I don’t ever make the claim that the Gospel accounts can be trusted, and most certainly I do not drop my criticism of the biblical text just because I think a criticism of Jesus will be more interesting. Rather, quite clearly in the book, I state that discussions of the accuracy of the Gospel records are important, but fall outside the purview of the limited scope of my argument. Do I think the Gospels are reliable on every point? Certainly not, as I make abundantly clear with extensive argumentation in multiple chapters of HFG. However, on the question of Jesus’ apocalyptic worldview and predictions, I am of the persuasion, following the broad scholarly consensus, that the Gospels portray Jesus fairly accurately. I believe Jesus was an apocalyptic prophet who wrongly predicted the end of the world. I do not believe that the Gospel writers made that up about Jesus. So the disingenuousness exists solely in Steven’s own mind, and not in reality. It also exists in his presentation of my argument. He continues:

Although he considers many alternatives to Jesus wrongly predicting His second coming, he throws them aside and simply asserts that Jesus was wrong.

This claim is utterly absurd. The chapter dealing with these issues is about 50 pages long, and I do not simply “throw aside” any argument. Rather, I take each position apart piece by piece, extensively, and carefully. Steven’s claim here borders on outright deception. I make no simple assertions. I mount an extensive and heavily supported argument from which I draw a conclusion, and a conclusion I personally do not like, as I note in the book as well.

However, there are still MANY more alternatives that Stark failed to consider. I don’t have the space to get into them here, but if you’re interested feel free to check out this link: […]

The link, unfortunately, was deleted by Amazon. Nevertheless, in an already lengthy chapter, I can’t be expected to refute every fringe idea out there.

Also, its important to note that some of Starks conclusions are drawn upon from the Documentary Hypothesis. I don’t know how much he’s adequately researched on this hypothesis, but its becoming a position that is gravely mistaken. A lot of OT scholars have adequately shown the major holes in this theory and its something that I presently think is a weak position.

Aside from Steven’s personal opinions about the Documentary Hypothesis, his characterization of its status within the scholarly community is grossly inadequate. While there have been many developments in the documentary hypothesis since its inception, it remains the consensus, broadly speaking, of biblical scholars actively working within the guild. There are disagreements about dating of the sources and about certain texts and to whom they should be attributed, but that there are at least four clear and ideologically-opposed sources comprising the Pentateuch is not a hypothesis that is going away anytime soon. I don’t know how much Steven “has adequately researched on this hypothesis,” but my research includes having read close to fifty monographs and scholarly articles on JEDP, including the criticisms of JEDP by Cassuto et al. Once again, the fact that some scholars don’t hold to the consensus doesn’t make the consensus any less the consensus. And usually, a consensus is a consensus for good reason, and that happens to be the case with JEDP. Steven continues:

In Thom’s last chapter he valiantly attempts to provide some answers on how to adequately view scripture. In my view, his explanation falls short. If the Bible doesn’t accurately portray God and if it really cant be trusted then why bother calling yourself a Christian?

This displays Steven’s “all-or-nothing” logic, a logic that he shares with other fundamentalists but does not share with me. I can’t make my reasons for being a Christian make sense to him, but unlike fundamentalists, that isn’t my goal either.

His answer to this objection lies in his upbringing and the fact that the Bible has molded him into the person he is today. And? That is an extremely poor reason Mr. Stark.

I’m sorry Steven thinks so. Of course, those aren’t the only reasons I listed, and I have more which I didn’t list in the book. But I’m sorry Steven thinks my reasons for being a Christian are poor. But there’s nothing I can do about that, other than to say that the fact that the Bible has shaped me in ways I’ll never exhaust is more than enough reason to call myself a Christian. The fact that I love and want to emulate Jesus (despite his flaws) is also more than enough reason, a reason I offered in the book which Steven (for whatever reason) failed to mention in his review. He continues:

So, if he was raised as a Muslim and it was the Koran which had molded him, would he then be making the same statement towards Islam? Would he still consider himself a Muslim?

Um, yes. That’s the idea.

Also, if the Bible cannot be trusted to adequately reveal the character of God then why view the Bible as anymore special than the Koran or the book or Mormon? If this is all the closure Stark can provide then Im afraid his view of Christianity is inadequate. Obviously, these are my own opinions and I dont mean to come down too hard on Stark but it really makes me question why he would even call himself a Christian.

Steven of course has the right to question why I call myself a Christian. Long story short, my reasons are very different than his reasons. Of course, my argument (despite Steve’s consistent portrayal of it) has never been that “the Bible cannot be trusted to adequately reveal the character of God.” Those are his words, not mine. I’ve argued that in places it gets God wrong. But I’ve also argued that in places it gets God right. Steven’s questions here for whatever reason ignore the most substantive sections of the final chapter he is critiquing, in which I argue that we must exercise critical reasoning when appropriating the biblical texts as guides for our lives in faith communities. The same is true of any set of sacred texts, or any set of texts at all. The whole point is that we don’t have that book that has come down from heaven the likes of which we can turn to for answers without needing to exercise critical thinking. We don’t have it, and no one does. That’s a humbling position. Which is why when Steven accuses me of trying to fit God “nice and neatly in[to my] ‘Christian’ box,” I am humorously taken aback. Rather, the whole point of my book is to expose the many ways we humans have written and used “scriptures” to fit God into the boxes of our own devising, and to state that faith is what it means to abandon those boxes—to navigate the world without always having clear answers and a clearly defined object of faith.

As for Steven’s charge that I “cherry-pick the evidence to weigh in the favor of [my] liberal Christianity,” again this is a charge Steven has failed to substantiate. His one attempt to do so (in reference to Jeremiah 19:5-6) was an abject failure, displaying that it’s not my argument which is weak, but Steven’s ability to comprehend it.

That said, I do appreciate Steven’s cordial tone throughout most of his review, and I’m grateful he’s brought up the issues he has. I wish him all the very best.

Posted: June 25, 2011 at 2:37 am

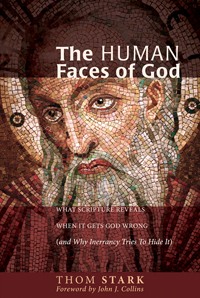

Thom Stark’s The Human Faces of God is a book that deserves a wide readership. Although this book may appear slim, it packs quite a punch and manages to get a lot done in a short amount of space. It is in part a summary of the current state of affairs in modern biblical scholarship, a rebuttal against biblical inerrancy, and a moving testimony of a man who has spent a lot of time evaluating the scripture that he loves and coming to terms with it on its own grounds.

Many Christians may feel threatened by Thom’s new book, but as a devout Roman Catholic, let me tell you that Thom’s book is anything but threatening. Although the title may appear provocative this book is not an attack on biblical values and Thom does well to critique the ‘ugly’ part of our holy scriptures on it’s own ground, by using the values he derived from it. He moves through the many portraits of God as presented in the Biblical text and sensitively notes how some of them have been used to enact despicable acts of cruelty and violence against those we don’t particularly like. While he does this, he also engages in dialogue with many apologists, both old and new, and criticizes their efforts to explain away some of the more horrifying passages in the Bible. His honesty in doing so is very refreshing and I commend his efforts in showing just how far inerranists are willing to go to defend their positions, however dishonest they are.

And speaking of inerrancy, Thom’s dialogue with it is worth this book’s weight in gold. Mr. Stark, convincingly shows that inerranists are far from being “loyal to the text” as many of the new atheists would have you believe. Inerranists, as Thom demonstrates, often fail to realize just how diverse the biblical worldview is and far from being faithful to it, they tend to impose their own interpretations of scripture [as they think it should be] onto the text itself and twist everything that says otherwise to conform to their own worldview. The Bible deserves better and toward the end Thom sits back and thoughtfully considers what to make of scripture, now that he sees just how human and fallible it is in some places. His answer will surprise many, but it’s worth being heard.

Overall, Thom Stark’s The Human Faces of God is an excellent book. It’s short, easy to read, and accessible. It honestly presents the findings of modern biblical scholarship in an understandable way, and it gives us a worthy alternative to fundamentalism. So, buy it, read it, and be amazed.

5/5 stars

Posted: April 6, 2011 at 8:47 pm

UPDATE (04/13/11): Dan has given a short response to my response below. I’ll quote it here and then offer another short response:

[Stark] has a tendency to try and refute critics by talking and talking and talking until nobody gives a damn about the subject at hand (I think he seems to be mistaking the silence of the opposition for something more than that [agreement?]… although maybe he is just happy with the silence). Regardless, I’m not convinced by everything he writes in his response (by the end of it, you’ll notice that my review never actually accurately reflects anything in Stark’s book… that made me chuckle!), but I am happy to give him the opportunity to clarify points that certainly were not clearly stated in The Human Faces of God.

I appreciate Dan’s original review because it did force me to be clearer about aspects of my argument that were given shorter shrift. My response (below) was certainly not an attempt to silence Dan, and I do not mistake silence for agreement. I respond in detail to certain critics because I want to clarify my position, where I think I have been misunderstood, so that, once I’m understood, if real disagreement remains, we can actually talk about that real disagreement. Dan and I do have very real disagreements. For instance, we disagree on the question of whether Jesus and Paul expected an imminent divine intervention. But much of Dan’s critique wasn’t a critique of my actual position, so I’m not sure whether Dan and I really disagree on those points or not. That’s why I labor to be perfectly clear, so that if there is real disagreement, it can surface, and we can talk about it (if Dan or anybody else wants to).

Now, admittedly, in light of the negative tone that surfaced in various places in Dan’s original review, I had to struggle a bit to respond evenly and kindly. I did my best, and I think it’s clear that I was trying (both here and on the thread on Dan’s blog), but if there is one thing I would change now about my response (below), I would replace most instances of “This is a mischaracterization of my position” with “Allow me to clarify what I was trying to say.” If I had done that, perhaps the length of my response wouldn’t indicate to Dan that I’m trying to beat him into submission, which I’m not. I value discussion, especially discussion that is marked by charity and goodwill.

Now, Dan says that I claim at the end of my review that he “never actually accurately reflects anything in [my] book.” But I didn’t say that. I said that he had an inability to read what I write within the context of his claims that I am rooted in an American script. In that particular case, he misquoted me as having said that we don’t “need” a divine intervention, when in reality all I said was that we don’t need to wait for it. There’s a big difference. I agree with Dan that we probably need a divine intervention if we’re going to get out of this mess, but I think we should be working to resolve our structural, systemic issues, even (or especially) if no such divine intervention is forthcoming.

Nevertheless, I didn’t claim that Dan never got me right. Dan accurately reflected a lot of what I wrote, but he also got a lot wrong, and I am more than happy to take the blame for that in most cases. But in some instances, where Dan accuses me of being rooted in an American script, for instance, I think Dan’s readings of me in those cases reflect more about him than about me, which is not meant as an insult. I am not accusing Dan of intentional mischaracterization. And I have no desire to malign him in any way. My intent was not to shut him up. My intent was to clarify my position. I may be verbose, and I’ll plead guilty to that.

Once again, I wish him the very best, and once again, I’m grateful for his challenging review.

——————————————–

My thanks to Dan Oudshorn for taking the time to write a substantive critical review of my book. In his review, Dan raises some important issues, makes some good criticisms, and also makes several criticisms that are wide of the mark, displaying inattention to elements of my argument that are clearly stated within the book. Some of Dan’s criticisms also involve assumptions about my personal life and involvements which are mistaken or inaccurate, and on the basis of those assumptions he takes an uncharitable approach to elements of my language in the book. Nevertheless, Dan does state that, “all things considered, this is a very good book and one that I would recommend to those who value the Bible but who have wrestled with it and find themselves dissatisfied with the proposed solutions that they have encountered thus far.” So in stating that some of his criticisms (to be examined below) were uncharitable, I do not mean to state that the review as a whole has that tenor. It is a very good review, and I am grateful to Dan for raising the issues he does raise.

In this response I’ll engage Dan’s criticisms in some detail, piece by piece.

First, Dan says, “Stark builds a convincing case, even though he doesn’t necessarily break any new scholarly ground (as John Collins notes in the forward).”

Yes, and as I myself articulate clearly in the preface. The intention of the book was not to break scholarly ground (although I did mount several arguments in response to certain scholars that have not appeared to date anywhere in print to my knowledge), but rather to make the existing scholarship accessible to the average church-goer.

Regarding my ninth chapter, Dan writes that “he examines and rejects both Brevard Childs’ ‘canonical’ reading of the Bible, as well as more ‘subversive’ or counter-imperial readings.”

This is in fact a misconception about my ninth chapter that other reviewers have had, which indicates that I wasn’t clear enough that I do not reject these approaches per se, but rather find them inadequate on their own as a way of managing the problematic texts. For instance, with regard to the subversive readings adopted by the Horsley school, I’ll just note that folks like Horsley and Elliott themselves do from time to time point out what Schussler Fiorenza argued more programmatically in The Power of the Word, namely, that there is the danger that hidden transcripts will be counter-subverted, and therefore are not a permanent solution to the problem. I just think that concession isn’t given enough space in their writings, and so I added my “vote,” as it were, to that side. But as I point out on pp. 214-16, the subversion of the public transcript by the dominated classes is the best they can do in their situation, and that I am not rejecting that strategy, but rather calling for those of us who are free to do so to move beyond the categories they had to employ for their own survival. My point in chapter nine was not that subversive readings are “bad,” just that they are incomplete deconstructions of worldly power. Necessarily incomplete, and it’s our responsibility to complete them.

Next Dan claims that my “understanding of our contemporary context needs to be sharpened. On multiple occasions, his deployment of current or recent points of comparison is sloppy or problematical. For example, on multiple occasions he compares the texts about the conquest of Canaan to the American history of conquest over the First Nations peoples. Unfortunately, he always refers to that American genocide as though it were a distant past event (cf. p123). This is simply not the case and the popular State- and Corporate-sponsored oppression, exploitation and genocide of First Nations peoples continues up until this present moment. In this regard, Stark is still too deeply rooted in the dominant script of America.”

This is an untenable accusation, and one that pays no attention to the context in which my references to Native American genocides appear. I am well aware of the continued oppression, exploitation and genocide of the Native Americans that takes place in the U.S., in Canada, in Mexico, and in Central and South America. Dan references p. 123, where I use an analogy to highlight the fact that the Israelites slaughtered the Amalekites for a battle that occurred four hundred years in the past. The analogy was a hypothetical scenario in which a contemporary group of Cherokee slaughtered all of the residents of Tulsa, Oklahoma as retaliation for a battle that occurred four hundred years back in history. Dan thinks this means I am unaware that Native Americans continue to be subject to grave injustices to this day, and that I am “too deeply rooted in the dominant script of America.”

First, this was a hypothetical analogy, not a depiction of actual events, and was thus rooted in an imagined scenario. In my imagined scenario, the Cherokee were retaliating for a battle four hundred years ago; in my scenario, they were not retaliating in response to their long history of exploitation by the State. That was the fictional picture I was painting to make my point. In nowise does this mean that I am unaware of the continued exploitation and genocide against Native Americans, and in nowise is it a reflection of my being allegedly rooted in an “American script” that posits the injustices as a thing entirely of the past. Every analogy has its limitations, and if pressed beyond those limitations breaks down. Now perhaps Dan might respond that if I am aware (as here I “claim” to be) that Native Americans continue to this day to be oppressed, then it certainly doesn’t show in the book. Yes, that’s right. Because I wasn’t writing a chapter about Native American genocide. I was writing a chapter about Canaanite genocide, particularly as pictured in Deuteronomy and Joshua. Just because I didn’t mention the current plight of Native Americans doesn’t mean I’m blind to it. I also made analogical reference to the Nazi Holocaust, but I didn’t make reference to the continuing reality of anti-Semitism and the pervasiveness of portrayals of Jews as subversive, greedy, threatening, etc., in the U.S. and throughout the world. Does that mean I’m not aware of these realities? Hardly. It just means that such a discussion fell outside the purview of my argument about an ancient book. What reference I did make to the Holocaust and the Native American genocides were limited analogies to shed light on that ancient book.

Nevertheless, Dan continues:

Another example of Stark’s rootedness within that script, comes through in his comments about current American wars, which he refers to as “ambiguous” (p222). A few pages later, it’s as though Stark forgets that America is even at war. When he speaks about the apocalyptic dualism between good and evil, he suggests that this dualism may be appropriate in wartime when “it is often necessary to draw up sharp dividing lines between sides in the conflict” but now things are no longer so black and white (p226; cf. 225-226). What Stark neglects here is that America is at war, not to mention the ongoing global class war of the wealthy against the poor that has been steadily increasing over the last several decades. Of course, lacking a strong understanding of our current situation isn’t a weakness unique to Stark. One often sees this amongst scholarly-types who are trying to be relevant but who aren’t sufficiently rooted amongst the marginalized and so end up making inadequate or misleading remarks despite their best efforts.

This is some charged rhetoric, but it’s clear once again that Dan is attributing to me claims I haven’t made. First, when I referred to U.S. wars as “ambiguous,” that was meant as a critique of the contradictory justifications the State and media have employed in order to legitimate them. This is hardly evidence that I am rooted within an American script. I’ll quote the entire passage, in context:

Today we denounce such practices [as human sacrifice] as inhuman and reject as irrational the belief that the spilling of innocent blood literally affected the outcome of harvests and military battles. Yet we continue to offer our own children on the altar of homeland security, sending them off to die in ambiguous wars, based on the irrational belief that by being violent we can protect ourselves from violence. We refer to our children’s deaths as “sacrifices” which are necessary for the preservation of democracy and free trade. The market is our temple and it must be protected at all costs. Thus, like King Mesha, we make “sacrifices” in order to ensure the victory of capitalism over socialism, the victory of consumerism over terrorism. Our high priests tell us that it is necessary to make sacrifices if we are going to continue to have the freedom to shop. Unlike King Mesha, however, in our day it is rarely the king’s own son who is sacrificed; rather, the king sacrifices the sons and daughters of the poor in order to protect an economy whose benefits the poor do not reap. (As Shrek’s Lord Farquaad so profoundly put it, “Some of you may die, but that is a sacrifice I am willing to make.”) Like martyrs, our children are valorized because of their willingness to sacrifice their lives in yet another war waged to rid the world of war. We invest their deaths with meaning by forcing ourselves to believe, despite all evidence to the contrary, that their blood affects the productivity of the market and protects a multitude from the threat of violence.

God speaks to us through these texts, if we are willing to listen critically, and calls on us to recognize ourselves in them. When Yahweh demands the sacrifice of Israel’s firstborn children in exchange for freedom from slavery to the Egyptians, when he provides victory in battle in exchange for the pleasant odor of human carnage, we see another of the many human faces of God in scripture. Despite all our pretensions to progress, it seems that there is nothing more human than to hope that our futures can be secured by delivering up our young as lambs to the slaughter. (222)

The above passage, read in its entirety, shows that I am not only well aware, but also thoroughly critical, of the very things of which Dan has accused me of being blind. So when Dan writes that “what Stark neglects here is that America is at war, not to mention the ongoing global class war of the wealthy against the poor that has been steadily increasing over the last several decades,” it is clear that his accusation is sterile. I clearly and unequivocally state in the passage quoted above that not only is American perpetually at war, it is perpetual a war that has everything to do with class and capital.

Dan claims that, “a few pages later, it’s as though Stark forgets that America is even at war. When he speaks about the apocalyptic dualism between good and evil, he suggests that this dualism may be appropriate in wartime when “it is often necessary to draw up sharp dividing lines between sides in the conflict” but now things are no longer so black and white (p226; cf. 225-226).”

Dan completely misrepresents what I’m saying here. I’m not denying that we are currently at war when I say that things are no longer so black and white. Read in context, what I’m saying is quite clear, in fact, and I’m baffled that Dan can be so confident in this accusation. In context, I’m discussing the apocalyptic worldview of first-century Jews, and articulating that the intense demands of discipleship Jesus required of his followers was connected to his belief that the world was in the last stages of a cosmic conflict between the unseen forces of good and evil, a conflict that is to have its culmination, according to Jesus’ belief, within a matter of no more than a few decades. Thus, his call to celibacy, and his demand that his disciples leave their families behind, is rooted in this idea that the world as they knew it was about to come to an end. I argue that such a demand makes sense in light of Jesus’ expectation of an imminent end, and anyone who followed the demand could be considered courageous if it were true that the cosmic battle is really coming to a close within their lifetime. And here is where Dan gets hung up on another of my analogies. I use a “war-time” ethic as an analogy for this apocalyptic perspective. In war-time, a man (a soldier) is considered courageous for leaving his family and going off to fight in what’s considered to be a righteous war. But when it’s not war-time, a man who left his family would not be considered courageous at all, but rather he would be considered irresponsible. I contended that perhaps when some Jews, although wishing that Jesus’ belief in the imminent end were true, chose not to leave their families to follow Jesus, they were making that decision not out of cowardice but out of courage. The belief that one’s own time is the ultimate and climactic period of human history is certainly not a belief unique to Jesus and his early followers, but it’s one that can be very enticing. Many Jews would have wanted Jesus to be right, but perhaps they saw that Jesus was just one apocalyptic prophet among many in that period, none of whom got it right, and therefore, although they wished God was about to intervene as Jesus preached, and were tempted to leave their ordinary responsibilities toward their impoverished families in order to follow him, chose instead to be courageous by grinding it out within their communities, struggling for survival in a world where the prospect of real divine intervention looked bleak. As I stated perfectly clearly in the book, “perhaps they [those who didn’t follow Jesus] saw joining yet another radical revolution as the coward’s way out of the harder task of commitment to one’s family and everyday responsibilities in the midst of a crippling economy and violent world” (226).

My point, therefore, was that those who didn’t follow Jesus were only cowards if Jesus was right that God was about to intervene. But if he was wrong, then perhaps those who didn’t follow him took the more courageous path.

Now, Dan gets hung up because I use “war-time” as an analogy. But again, it’s a limited analogy. I do not mean to say that, absent an apocalyptic war of the kind Jesus envisioned, all we have is peace time. No! There is always war, and not just military wars, but wars at home. Those are the real wars that impoverished human beings have to wage every single day, as Dan well knows. And that was my point. Perhaps those who didn’t follow Jesus’ exacting demands weren’t being cowards, but were choosing instead to be courageous warriors in the struggle for subsistence survival in impoverished communities that had by then heard one too many doomsday prophets to buy into the notion that all their woes were about to be fixed in one fell swoop by a divine intervention. After all, it’s the ideological wars of States that call impoverished men and women to sacrifice their struggle at home for a mythical, ultimate battle against the forces of evil. In the same way, Jesus’ call for men to leave their families to engage in just such an ultimate, cosmic battle against the forces of evil undermined, in this limited sense, his concern for the poor if in fact he was wrong about the imminent ultimate conflict, as I argued he was.

Dan’s attempt to paint my statement that “morality is not always black and white” as an indication that I am somehow forgetting that we are currently (and perpetually) at war just displays that Dan doesn’t understand the analogy I’m making. I am not claiming, as he claims I am, that because we’re not “in wartime” then Jesus’ wartime ethics don’t apply. The argument I’ve made is that if Jesus did predict that human history was about to culminate in an epic battle between good and evil in real history, then Jesus was wrong, and his specific “wartime” (a metaphor) ethic doesn’t necessarily apply. And as I pointed out, if he was right, then the ethic holds, but if not, then the ethic itself becomes a catalyst for oppression and injustice as it gets stretched out over centuries and millennia, when it was really only intended to be applied to a short span of time. We need long term strategies for resistance to injustice, and long term goals for restructuring society around justice. While short-term survival strategies are always necessary, they are not enough, unless the world is actually about to end. That’s my point.

So Dan writes that, “of course, lacking a strong understanding of our current situation isn’t a weakness unique to Stark. One often sees this amongst scholarly-types who are trying to be relevant but who aren’t sufficiently rooted amongst the marginalized and so end up making inadequate or misleading remarks despite their best efforts.” And it’s clear that Dan has entirely missed my point. To be sure, what he describes here is a real problem, and it may be that I am susceptible to this problem in various ways. But in this case, the evidence Dan provides to suggest that I am susceptible to this is actually, when properly understood, evidence to the contrary. What Dan is saying I overlooked was precisely the point I was making.

Next, Dan criticizes my own criticisms of canonical and subversive readings of the Bible. He writes: “It seems to me that Stark (a) doesn’t sufficiently engage the possibilities inherent to some of those readings; and (b) does not recognize the extent to which he himself relies upon, and employs, both of these ways of reading.” He continues:

Beginning with Childs, Stark describes his canonical reading in this way:

“If the texts are going to continue to be useful, they will be useful not as objects of historical curiosity but as dynamic scriptures which are the rightful property of the community of faith… with the intention of providing the community of faith the inspiration it needs to be faithful in a trying world. As a result, readings that challenge the truthfulness of this or that text… render the texts useless for their intended purposes” (p211).

Stark then identifies three problems with this: (1) the final form of the text was not chosen by the community of faith but by the theopolitical elites; (2) diverse voices are lost and problematical texts are buried; and (3) no clear determining factor exists as to who determines the what “canonical reading” actually is (p211-212). This is fair enough, but it seems to me that Stark only engages in a slightly tweaked variation of this reading, and a tweaking that is susceptible to [the] same criticisms. Thus, in treating some scriptures as “condemned texts,” he asserts that what readings are appropriate will vary from context to context and that “each confessing community must decide for itself how to make these and other texts useful for its own purposes” (p219). Later, he again affirms that “the proper place for critical appropriations of scripture is within the believing community” (p235). To me, this sounds a lot like a canonical reading and one that is still exercised without clear determining factors as to what might make this reading valid.

Now, this is a useful criticism, but one that mischaracterizes my position. My third criticism of Childs (which is also one of Brueggemann’s criticisms of Childs) is that his readings of the text can be susceptible to being arbitrary. By positing an “overarching narrative” through which he reads all the texts, he often muffles the various contending voices within the texts in order to conform them to this overarching narrative. The problem is it is not clear where this overarching narrative should come from. How do we determine what is the “right” overarching narrative?

Now, my position is that the texts need to be read historically-grammatically and with reference to all the necessary utilities such as source criticism, etc., first and foremost. So our goal is to read the various texts in their own voices, to let them say what they want to say, without imposing theological constructs of our own devising upon them, in effect changing their voice. But here’s the crucial point: it is our application and appropriation of the texts, within the community, that is open for discussion. And as I articulate on numerous occasions in my final chapter, that discussion is one that doesn’t terminate, and the choices that are made about how to apply and appropriate the texts are choices that must be made in specific contexts, according to the needs of each community. This is not arbitrary, but contextual, and is the product of a continuing discussion that draws upon the various voices in scripture in order to discern what the community must do as it seeks to resist injustice and engage the world. In short, my position is that there can be no “clear determining factors as to what might make this reading valid,” if by that Dan means to refer to factors that transcend specific contexts. While Childs wants to posit an overarching narrative within which to understand scripture, I reject any overarching narrative at all (both within scripture, and within the community) that should be used to control our application and appropriation of scripture. Rather, the various voices in scripture must be brought into conversation with a variety of competing narratives that are rooted in the real experiences of the believing community, from context to context. The process is not arbitrary; far from it. It’s the opposite. It’s contextual.

Dan continues:

I’m not sure if Stark goes beyond “burying” problematical texts. Rather, instead of burying them, he rejects them, but his criteria for doing so seem just as arbitrary as Childs. That is to say, while Childs (as a representative of a believing community) may be less committed to the truthfulness of a text and, by that means, escape a harsh confrontation with some texts in order to affirm a God committed to life, Stark (as a representative of a believing community?) confronts the same text in order to own it by condemning it, thereby ending up in the same position.

This is a mischaracterization of my position on a number of levels. First, I do not “reject” the problematic texts, and I do not “own them by condemning them.” I condemn them, but in doing so, own them. That means, condemning the problematic texts is not a matter of “rejecting” them, but of holding them closer still precisely because they reveal condemnable aspects even of our modern selves. We need the problematic texts in our scriptures as a mirror of our own problems, so that we can see what they are.

Now, to Dan’s claim that I end up in the same position as Childs. Emphatically no. Childs bypasses the confrontation of the text, thereby making his “life-affirming” readings of the text susceptible to ideological infiltration by the problematic texts he glosses over. In Childs’s approach, our condemnation of the texts remains unconscious, and for that reason we are unconsciously susceptible to their influence. So although Childs and I both want to appropriate the texts in life-affirming ways, my strategy insists on a conscious confrontation of the problematic texts so that when we get to the point where we are making life-affirming use of them, the community will be much less susceptible to the infiltration of the problematic texts’ death-dealing ideologies. That’s why Childs and I do not end up in the same place, despite the prima facie appearance that this is so. One hermeneutic reflects an unconsciousness, the other is a pursuit of a robust consciousness. Having said all that, I am glad Dan made this criticism, even though it misunderstood my position, because this is an important point to bring more clearly into the light.

Dan continues:

For all its stronger commitment to historical criticism, Stark’s proposed reading ends up sharing a great deal in common with the inerrantists with whom he is arguing: both permit prior commitments to dominate their readings of the Bible. Just as historical criticism cannot be used as the basis for belief in biblical inerrancy, so also historical criticism cannot provide Stark with the criteria needed to determine if this or that text is condemnable. As much as Stark rightly criticizes inerrantists who propose “plain” readings over “literal” readings (i.e. who permit an ideological overcoding to provide a previously determined meaning for any given text), we see the same ideologically-motivated methodology at work when Stark describes the “condemned texts” in this way:

“Through these texts the voice of God speaks to us today, calling us to reject self-serving ontologies of difference, to abandon any allegiances to tribes or nation-states that take precedence over our allegiance to humanity itself and to the world we all inhabit (p120 [sic, actually p. 220]).”

Of course, the condemned texts literally say nothing like this. So, while I find Stark’s approach to have a better ethical value than the approach taken by the inerrantists, their hermeneutics may be more similar than both parties care to admit.

This criticism is another important one, that again misunderstands my position. Dan claims that I “permit prior commitments to dominate [my] readings of the Bible.” But this is not so, at least according to my ideal. Dan is missing the distinction between my reading of scripture on the one hand, and my critical appropriation of scripture on the other hand. This is a crucial distinction that Dan misses, allowing him to level this charge. I’ll elaborate.

My hermeneutic is to read the various texts (many of them composite) historically-grammatically, in order to discern the voices of the various authors and get a clear sense for what they want to say. That is my reading of the text. In this part of the process, I do not want to impose my own judgments about the text onto the texts. (Obviously there are potential biases or sometimes just a lack of data that will prevent me from getting a text just right in terms of finding the author’s voice, but the ideal is to root those biases out and to be honest when there is insufficient evidence.)

Now, once we’ve found the author’s voice, then it becomes incumbent upon us to engage in dialogue with the text, and to make any criticisms we think are necessary. This is the part of the process where the texts, in their own voices, are critically appropriated for the purposes of the community. This is not at all the same thing as the inerrantists who blindly insist that their reading of the text is what the text is saying, unaware that their assumptions are disfiguring the various voices therein. I’m surprised that Dan missed this, because I discuss this distinction at length in the final chapter, under the heading, “Everybody Chooses.” I’ll quote an excerpt from this section at length:

The criticism that the inerrantists make of critical readings of scripture is that they are arbitrary. They accuse readers of arbitrarily picking and choosing which are the “condemned” texts and which are the “inspired” ones. Or rather, they accuse readers of dismissing the texts they do not like, and retaining only those the so-called “liberal worldview” can stomach. Again, however, as we have seen, the inerrantists are no less guilty of picking and choosing which text they believe and which they deny; it is only that inerrantists hide their disagreement with certain texts by reinterpreting them to conform to the texts they prefer. Inerrantists pick and choose; they simply do not or cannot admit to it. What I am calling for is honesty in this process. We all emphasize certain scriptural perspectives to the neglect of others. I am suggesting that being conscious and open about that fact will actually help to prevent us from being selective arbitrarily and will force us to struggle to find good reasons to make the choices that we make. Everybody makes the choices. If they do not realize they are making the choices, then they are more susceptible to having made those choices arbitrarily or for poor reasons. The process of determining which texts to condemn and which to affirm, or which texts to read with caution and caveats, is a process that must not end. It is a struggle that each generation must take up anew, as they seek to be relevant actors in their societies with the Judea-Christian scriptures as a resource. (235-36)

Dan quotes me saying that “through these texts the voice of God speaks to us today, calling us to reject self-serving ontologies of difference, to abandon any allegiances to tribes or nation-states that take precedence over our allegiance to humanity itself and to the world we all inhabit” (220). He then comments that “Of course, the condemned texts literally say nothing like this.” That’s correct. They don’t! And that’s my point. He misses another important distinction, which is very clear in the argument.

The distinction is between the human faces of God which are in the text on the one hand, and the voice of God which speaks to us today through these human texts, calling on us to recognize our own deficiencies in the deficiencies of the human texts. So, contrary to Dan’s portrayal of my position, it is not that “the texts” tell us to “reject self-serving ontologies of difference.” The texts tell us to embrace them! Rather, it is God—speaking through the human texts as we come to them to hear God’s voice—who calls us to reject those self-serving ontologies.

And again, as I state in several places, the process of determining what the texts say, and the process of determining how to critically and constructively appropriate what the texts say, are two separated but necessarily related processes, and they must, I argue, be carried out in that chronological order. We can’t know how best to appropriate a text for a community until that text is heard in its own voice, because if we are not conscious of what that voice is saying, we are susceptible to its infiltration either now, or later on down the line. But the second process, the process of figuring out how to appropriate the texts, that is the process of listening for the voice of God. In short, the first process seeks to hear the voices of the Biblical authors. The second process seeks to hear the voice of God. They are related, but cannot be confused. Inerrantists (always) and canonicists (often) confuse those two distinct processes, and that’s what I argue gets us into trouble.

Perhaps Dan wants me to articulate some clear system by which the “right” appropriation of the texts may be secured; this seems to be the need lurking behind his criticisms here. My response is that there is no “right” way to do this. The “right” way to do this will vary from context to context, and I, as an individual, cannot determine what this is on behalf of any community. This leads us into to Dan’s next criticism:

I’m curious to know how Stark’s reading is one that is really produced by a “believing community.” It seems to me that his reading is produced by one person struggling to make sense of scripture (one person, it should be noted, who also is rooted more amongst the elite than the oppressed). I don’t know how it is the result of a “confessing community” struggling to make sense of the Bible. I’ve heard from others that Stark operates in isolation from faith communities so I don’t know if he follows the methodology he prescribes. After all, Stark concludes with some pretty individualistic and personal words: “I am proposing [this reading] because to me it represents the most honest struggle–it is the only way that I know how to navigate our moral universe” (p241, emphasis added; no real sign of any “believing community” here).

There’s a lot to unpack here. Dan continues to misconstrue my argument, this time rather egregiously. First, to answer his questions:

My reading of these texts is the product of intense personal struggle, and struggle with other Christians in various Christian communities. They began years ago, during my undergraduate studies, where I was engaged in a home church community, and where I was also a fully participating member of and Sunday School teacher in a United Methodist church. They have continued to the present. I currently do not attend a church. Next month, however, my family is moving to Texas, where my wife and I will be working full time in another United Methodist church, and part of my involvement will include developing free education programs for impoverished and minority communities surrounding the church, and coordinating interfaith dialogue and cooperative interfaith work within the communities. This kind of work has been my vision for years, and now that I am about to finish up my graduate coursework, I am excited about diving into it. I don’t know who the “others” are from whom Dan has heard that I “operate in isolation from faith communities,” but whoever they are, they clearly aren’t close enough to me to know who I’m engaged with, where I’ve been, and where I’m going.

Now, what Dan’s questions/criticisms here entirely miss is what I clearly stated in my book twice, once at the beginning of my proposed appropriations of the problematic texts, and a second time at the end of that section. I’ll quote what I said in order to show how Dan’s criticism here is a flagrant mischaracterization of what I was doing in the final chapter:

These are my own applications of the text, and I do not pretend that they are necessarily the right or the only applications that should be drawn from the text. Of course, what is the appropriate use of the text will vary from context to context. Each confessing community must decide for itself how to make these and other texts useful for its own purposes. In what follows I am merely attempting to show how it is possible to hear God’s word, despite it. . . . These have been my own attempts, and I do not pretend that my musings should take the place of the discernment of the community. Each community must decide for itself how to make these and other texts useful for its own purposes; I have only made a few suggestions in the hope that my readings may prove useful to some. I have wanted to show how it is possible to hear God’s word, despite it. Beyond my own proposed readings, however, my argument has been that we must be honest with our scriptures, and that in many cases confrontational readings must be adopted, if we are to be honest with ourselves. (pp. 219, 231, emphasis in the original)

So, when Dan implies that I am being inconsistent if my proposed applications of the text weren’t derived from a community’s struggle, he is being disingenuous. I clearly state, twice, that the purpose of providing my “proposed” applications was to demonstrate the kind of thing I’m talking about. The purpose was emphatically not to say that my suggested appropriations are what every or even any community ought to adopt.

That said, many of the appropriations of the text that I modeled in that chapter were forged out of contexts in which various voices in my Christian community contributed to a way of engaging these texts constructively. This began in a house church, continued in an “established” church, and will continue in new contexts as I find myself within the graces of various communities.

Now, that said, there is nothing inconsistent about having personal readings of scripture, and struggling as an individual with the text. In fact, everyone must do this. But when it comes to the question of how to appropriate scripture within and for a community, these personal struggles and ideas must be brought to the table within the community for discussion. That’s how it works. The community then discusses, argues, agrees, disagrees, and finds ways to use the text that contribute to the life and work of the body.

The fact that I conclude my book with individualistic language, as Dan notes, is perfectly consonant with my position that the scriptures, insomuch as the church wants to use them, must be appropriated by the community. I conclude my book with individualistic language precisely because I wanted to refrain from imposing myself on those communities. These are some of the reasons I identify as a Christian, and this book is a reflection of a very personal struggle. But it is still a struggle that was born, continues, and will always continue, in dialogue with Christian communities and other communities among whom, by grace, I find myself.

Dan subsequently launches into a rather petty and inaccurately one-sided rehashing of an old dispute between us, to which I will offer no response, other than to say that if Dan wants to have that story, blessings upon him. I’ve put it all behind me. I harbor no ill will and I hope and expect that Dan and his work among the dehumanized will continue to thrive.

Moving on, Dan has a lengthy paragraph on my critique of subversive readings which assumes the misconception I’ve already addressed above, so I won’t revisit it, other than to state that it is not inconsistent for me to employ “subversive” readings and then to criticize them for not, in themselves, being sufficient. I can employ a subversive reading, but then go on to do the rest of the deconstructive work that completes the process. And as I pointed out in the book, people in contexts of domination are not to be faulted for keeping the subversive transcript hidden. The only point I’m making in that section of chapter nine is that the language of imperialism that was subverted in contexts of domination needs to be further deconstructed and, in fact, utterly dismantled and replaced, in situations where we can do that and not be publicly executed for it.

Now, on to Dan’s final point of criticism, my treatment of Jesus and Paul’s apocalyptic expectations. Dan writes:

All my previous criticisms have not been directed at Stark’s primary work in this text: exegesis. In fact, his exegesis is very strong throughout… except on this point. My first quibble is that Stark makes contradictory statements about the nature of Second Temple Jewish apocalypticism and never resolves them. Thus, on the one hand he approvingly quotes Dale Allison, who asserts that the apocalyptic perspective is marked by “a passive political stance” (p165) and goes on the assert that Paul espoused “a strategy of political quietism” because he believed the end of the world was imminent (p202). Consequently, he concludes that the apocalyptic perspective leaves “no room for any form of engagement… At most political responsibility is narrated in sectarian terms. To be politically responsible is to be sectarian” (pp226-27; emphasis removed).

On the other hand, however, Stark asserts that the apocalyptic system contained beliefs that were “politically explosive” and “freed one up to walk a dangerous path of hard-line opposition to Rome and to the puppet temple regime in Jerusalem” (p167). Further, he argues that Jesus’ (supposed) belief in the imminent end of the world functioned as a “pertinent sociopolitical/economic critique” and “was a complex beautiful, and incisively accurate expression of outrage at the existing world order, and a clarion call for fidelity to a new social system based upon justice rather than exploitation… it was the cry of the revolutionary spirit” (p229).

Thus, Stark concludes that the “revolutionary impulse was right… but the waiting for a miracle to make it happen–that was wrong” (p230). Thus, he rejects what he takes to be an apocalyptic “ethics of waiting” that removes us from the present pursuit of justice and “renders world history a cosmic joke” (p228; cf. pp227-28).

Dan’s criticism here misses the mark entirely. Although there is an apparent tension between these two facets of apocalyptic thinking, there is no real contradiction at all. First, I’ll quote John Collins from his seminal volume, The Apocalyptic Imagination:

The apocalyptic literature does not lend itself easily to the ontological and objectivist concerns of systematic theology. It is far more congenial to the pragmatic tendency of liberation theology, which is not engaged in the pursuit of objective truth but in the dynamics of motivation and the exercise of political power.

There are, of course, enormous differences between the view of the world advanced in the apocalypses and that of any modern liberationist. The apocalypses often lack a program for effective action. While the Maccabees took up arms against Antiochus Epiphanes, the “action” of the maskilim in Daniel was to instruct the masses and wait for the victory of Michael. In the wake of the destruction of Jerusalem, 4 Ezra and 3 Baruch divert their attention to the mysteries of God. The visionaries were seldom revolutionaries. Their strong sense that human affairs are controlled by higher powers usually limited the scope of human initiative. The apocalyptic revolution is a revolution in the imagination. It entails a challenge to view the world in a way that is radically different from the common perception. The revolutionary potential of such imagination should not be underestimated, as it can foster dissatisfaction with the present and generate visions of what might be. The legacy of the apocalypses includes a powerful rhetoric for denouncing the deficiencies of this world. It also includes the conviction that the world as now constituted is not the end. Most of all, it entails an appreciation of the great resource that lies in the human imagination to construct a symbolic world where the integrity of values can be maintained in the face of social and political powerlessness and even of the threat of death. (283)

So while it may appear to Dan that my statements that apocalypticism was “quietistic” on the one hand and yet “revolutionary” and “political” on the other hand are mutually exclusive, the fact is they are not. Many apocalyptic Jews had a radically revolutionary vision of liberation and of a just society, while at the same time advocating patience and quietism, in terms of direct engagement with empire, on the other. This quietistic strategy is underwritten by the assumption that God is about to intervene in history and liberate God’s people from oppression. Other apocalypticists promoted violent revolution, to be sure, but the Qumran sect, the apocalyptic community that produced Daniel, Jesus and Paul, and so many other Jewish apocalyptic movements rejected the violence in favor of patience, on the assumption that the salvific divine intervention was near.

For instance, The Community Rule, an apocalyptic text found at Qumran, says:

I will pay to no man the reward of evil; I will pursue him with goodness. For judgment of all the living is with God, and it is He who will render to man his reward. I will not envy in a spirit of wickedness, my soul shall not desire the riches of violence. I will not grapple with the men of perdition until the Day of Revenge.

The nonviolent stance here is informed by the assumption of a “Day of Revenge” in which God will vindicate the righteous over against their oppressors. Compare this with Paul’s language in Romans 12 and 13:

Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave room for the wrath of God; for it is written, “Vengeance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord.” No, “if your enemies are hungry, feed them; if they are thirsty, give them something to drink; for by doing this you will heap burning coals on their heads.” Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good. Let every person be subject to the governing authorities; for there is no authority except from God, and those authorities that exist have been instituted by God. . . . And do this, understanding the present time: how it is now the moment for you to wake from sleep. For salvation is nearer to us now than when we became believers; the night is far gone, the day is near. (Rom 12:19—13:1, 11-12)

The quietistic stance toward government, which counsels against direct action against empire, is informed by the assumption that God will take vengeance upon the sect’s enemies, and that, indeed, “salvation is near.”

So while the revolutionary vision and the radical critique of the system is there in Jesus and Paul, there is also an advocacy of nonviolence and patience, in light of the fact that their deliverance is at hand. Both The Community Rule and Jesus and Paul spoke of doing good to one’s enemies, and both movements also anticipated an imminent day of judgment on which God would vindicate those who waited for justice. Thus, my statements were not contradictory, and thus had no need to be “resolved,” unless one assumes that critiquing the empire and forming alternative sub-communities on the one hand, and taking a quietistic (i.e., nonviolent, no direct engagement, militarily or within the political system) approach to imperial domination on the other hand, are somehow mutually exclusive. They’re not.

And I should also point out that although Dan characterizes this as an example of a problem with my exegesis, I see no exegetical discussion going on here. This is a conceptual problem. Dan continues:

Stark’s remarks do not make sense of the actual activities of Jesus and Paul. Jesus and Paul did not exhibit any sort of political quietism. There were actively involved in working towards the goals of the just reign of God in the here-and-now of their moments in history. There was no passivity, no sitting back and waiting involved. That is why they were both condemned as impious terrorists and executed by the political authorities. Stark’s whole line of criticism falls apart when his picture of apocalypticism is compared to the textual witness to the lived lives of Jesus and Paul.

Yeah, either that or Dan is again mischaracterizing my argument. Take for example the language I used to describe Jesus and Paul’s activities in the final chapter:

The revolutionary impulse was right. The curse upon the existing world order was valid. The expression of hope in a new beginning was vital. The creation of counter-cultural communities which function as signs of this new beginning was not only noble but necessary in order for the revolution to be successful. But the waiting for a miracle to make it all happen—that was wrong. Now when I say it was wrong, I do not mean to condemn the early Christians. After all, Jesus and Paul were prudent to encourage their followers not to do anything that would bring the wrath of Rome down upon their heads. (230)

Maybe Dan just has a different definition of “quietism” than I’m using. Perhaps I used the wrong word, but I think that my subsequent characterizations of their activities should have made it clear what I meant. I don’t mean that they just sat on their asses and did nothing. And I don’t mean at all that they weren’t political actors. By “quietistic,” I simply referred to the prohibition on engaging in violent revolution, the prohibition on engaging in public protests against unjust policies (i.e., taxation; see Rom 13), and the obvious prohibition on attempting to achieve political power within the Roman system or the temple system.

But I clearly articulate that Jesus and Paul engaged in political activity, that they engaged in the formation of counter-cultural communities which were, in my words, “signs of this new beginning [that were] necessary in order for the revolution to be successful,” and in Dan’s words, “goals of the just reign of God in the here-and-now of their moments in history.” That’s the same thing. I agree with Dan that there was no “sitting back,” and I didn’t claim there was. But I disagree with him that there was no “waiting involved.” Certainly, it’s not idle waiting. (I never made that claim.) But there was certainly waiting, as is abundantly clear throughout the teaching of both Jesus and Paul. The waiting was for the divine intervention that would make their preparations for the coming of the kingdom worthwhile. But throughout the entire waiting period, they were to be making those preparations. This is perfectly clear in my argument, and I make this clear on a number of occasions. Here’s one example. In Acts 1:7-8, Jesus “does not deny that he intends to deliver Israel from Rome. He simply declines to tell them when. . . . Jesus does not want them fixated on the precise date; instead, he tells them that they will receive special power to testify about him in anticipation of his return. Pentecost is therefore presented by Luke as the empowerment of the disciples to prepare the world for the Messiah’s coming to restore the kingdom to Israel” (203-04, emphasis in original).

Now, Dan quotes me thus: “[Stark] concludes that the apocalyptic perspective leaves ‘no room for any form of engagement… At most political responsibility is narrated in sectarian terms. To be politically responsible is to be sectarian’ (pp226-27; emphasis removed).”

What I mean by this is not that early Christianity was nonpolitical, and not that it didn’t have a vision for the whole world, but that its interim strategy for the period before the divine intervention did not involve a strategy for transforming worldly political structures. Rather, it was the sectarian community alone that was to model what the whole world would look like after God intervened. Thus, “to be politically responsible is to be sectarian.” The Christian’s political responsibility was to “sign” the coming universal kingdom of God by reflecting its policies within the Christian communities. But Dan doesn’t quote my entire statement here. I go on to say that “this makes sense because the sect believes that what it is doing is directly connected to the fate of the entire world. The trouble is that the world is still waiting for the church to make good on that promise, two thousand years removed” (227).

If it’s still not clear, I’ll put it differently. The sectarian interim ethic of first century Christianity is not problematic in and of itself. I state this quite clearly on a number of occasions. It is right. It is necessary. And, because of the Roman domination system, it’s the absolute best they could hope to do. Where it fails is as a long term political program, world without end. It only works if in fact God is soon to intervene to make everything come out right. As I articulate later on the same page, “Jesus’ ministry of compassion was depicted as a sign of an impending new world order. Such charity was not a solution to the problem, but a glimpse at what the kingdom of God will look like when it comes. That may be all very well when the consummation of the kingdom of God is expected to take place within a few decades, but with a two-thousand-year margin of error, such charity itself becomes an injustice” (227).

A further way to articulate this problem is that, while the political program Paul developed within the churches—an astonishing international economic alternative to empire—was absolutely the right program for powerless groups under empire, failed, because of its inherent short-sightedness, to articulate a vision for justice beyond the bounds of the church. It didn’t anticipate a situation in which God never showed up to make the rest of the world look like the church. But that’s the situation we’re in, and thus (and I would have thought Dan would think this uncontroversial), we need more than charity and mutuality. We need to engage the world outside the church and seek to transform its own structures. We need a bigger vision than just a vision of justice within the church, and in order to achieve it, we need a bigger program than just a sectarian one. Why? Because God hasn’t shown up yet to fix the world for us.

So when Dan characterizes my position as a rejection of an “apocalyptic ‘ethics of waiting’ that removes us from the present pursuit of justice and ‘renders world history a cosmic joke,’” he misconstrues the nature of my critique. First, I never characterize the apocalyptic ethic as an ethic that “removes us from the present pursuit of justice.” On the contrary, the apocalyptic ethic is precisely to pursue justice by establishing it within the apocalyptic communities, while waiting for God to intervene and make the rest of the world look like those faithful (and just) communities. So I hope this clarifies for Dan what my argument actually is. What he’s critiquing isn’t at all my position. Dan continues:

Stark never adequately resolves the tension he sees between passive sectarianism and revolutionary action that I just mentioned.

That’s because I in fact do not see a tension between them. Dan continues:

Here, it seems to me that he has referred to some of the dominant scholarly voices who have studied apocalyptic literature, and he has pulled out key quotations, but he doesn’t seem to have delved fully into the discussion. Here, one notices the range of perspectives found within Second Temple Jewish apocalyptic traditions. Some voices are more passive and quietist, others are more active and revolutionary. Some are more reformist, others are more radical. Some are more rooted at the margins. Others are more rooted at centres of power. Given that, it is worth asking where Jesus and Paul fall within that spectrum. This would help Stark to not make contradictory statements.

As for the charge that I haven’t delved fully into the discussion: First, this is the longest chapter in my book and I had a lot to fit into it. Second, it’s not a whole book on apocalypticism; it’s just one chapter. Third, it’s a semi-popular book for a lay audience. So for that reason I tried to limit my engagement with other positions, rather than try to answer each and every objection that could come from any direction. I dealt with dissenting positions that are the positions normally represented in my target audience, and I gave a thorough and very close exegetical argument for my position.

Now, I am fully aware of the wide variety of political approaches in first century apocalyptic Judaism. I made reference to this fact on p. 229, where I noted that some were violent, while others were nonviolent. But I dissent from the characterization that the “passive and quietistic” voices should be presented in contrast to those that are “more active and revolutionary.” Yes, there were some militant apocalyptic Jews, in every period from the Maccabees to Bar Kochba. But as for the rest, I think the distinction between “passive and quietistic” on the one hand, and “active and revolutionary” on the other, is a simplistic one. The truth is that most apocalyptic movements were passive and quietistic in some respects, and active and revolutionary in other respects. All apocalyptic Jews were revolutionary, in the sense that they had a revolutionary vision for the world and made incisive, revolutionary critiques of Rome and often of the Temple regime in Jerusalem. And none of them were “passive and quietistic” in the sense that they just sat back and waited. Even the Qumran community, which was even more sectarian than Christians, was working to prepare for the coming battle between the forces of good and evil. Their withdrawal (which is disputed at any rate) was their form of action, and it was invested with revolutionary significance. So when I say that Jesus and Paul were both revolutionary and quietistic (I never in fact used the word “passive” to describe Christianity), I am not making “contradictory statements.” It’s just that Dan seems to have trouble understanding that Jesus and Paul could have different policies for how to engage different groups of people. You’ll note that Jesus never publicly and directly opposes Rome, but he does publicly and directly oppose the Temple regime. So, “passive,” in one sense, on the one hand, and “active,” in one sense, on the other hand. But even Jesus’ activism against the Temple regime didn’t have an immediate overthrow of the regime in view. He protested the temple (something Paul told the Roman Christians not to do against Rome), but he didn’t try to take it over. For that, he waited. Once again—active and passive, both at once.

Now, Dan’s next claim is, I must say (and I’m trying to be as nice as possible), utterly ridiculous:

My second quibble with Stark’s reading of apocalypticism is his acceptance of the thesis that both Jesus and Paul believed in the imminent end of the world (cf., for example, pp160-61 on Jesus and pp125, 199-201 on Paul). He doesn’t really argue the case for this but simply accepts the work of other scholars. [Emphasis mine.]

I don’t argue the case that Jesus believed in the imminent end of the world?! Is Dan kidding? Did he accidentally skip the thirty-one pages (pp. 168-199) of sheer exegesis I devote to arguing that Jesus believed in the imminent end of the world? I simply “accept the work of other scholars”? Seriously? In those thirty-one pages of exegesis, I barely make any reference at all to other scholars. It’s entirely my own close, careful exegesis of the text. The one scholar I do engage in this section is N.T. Wright, who I argue against, and not by citing “other scholars,” but by a painstaking process of critiquing his exegesis by my own exegesis! I am utterly baffled here. First, Dan says that his problems with my argument on Jesus and Paul are “exegetical” in nature, then he says I don’t do exegesis but just rely on other scholars. And not once does Dan actually contest a single point of my exegesis, not a single point from the thirty-one pages devoted to Jesus alone!

Now it’s true that when I got to Paul, I made shorter work of it. Why? Because the chapter was called Jesus Was Wrong, not Paul Was Wrong. After 35 pages arguing that Jesus was an imminent apocalyptic thinker (31 of which were exegesis), my intent in the concluding section of the chapter was to show that the early Christians’ views were consonant with the case I had just made for Jesus. But with Paul, contrary to Dan’s characterization, I still argued from at least seven separate Pauline passages from almost as many Pauline books. Dan critiques me because I only cite two scholars in support of my thesis on Paul (J. Christiaan Beker and J. Paul Sampley). But the claim that I made no real argument is flatly untrue. And, moreover, the thesis that Paul believed in an imminent parousia is hardly controversial! Even the most ardent Evangelicals (remember my audience) readily accept this about Paul, while wishing to deny it about Jesus. Thus, Jesus got more shrift because his was the tougher sell. And contrary to Dan’s claim that my position was the dominant scholarly position twenty years ago but is no longer dominant today, it remains the dominant position by a longshot. Yes, there is ample dissenting literature, but no more now than there was in times past. And not every Paul scholar who adheres to the dominant position writes a book on Paul.